52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 9—A Mystery Man

Great-grandfather, who are you?

Great-grandfather, who are you?

The identity of one of my great grandfathers remains a mystery to me. My grandmother Grace Riddle Reed stated that she did not know her father’s name and never met him.

Grace was born on a homestead near Palisade, Nebraska on August 30, 1896. Her mother was Laura Riddle, and Grace had three much-older brothers (probably half-siblings), Francis, Lewis, and Joseph.

Laura was supposed to have been married in Michigan in the 1870’s to George Edmonds although no marriage record for them has been found. George seemed to be out of the picture by the time Laura relocated to Nebraska with her sons in the mid-1880’s. By then, Laura had resumed using her maiden name Riddle, and her middle son Lewis went by that surname, too. Francis and Joseph continued to go by the Edmonds name. As far as I know, Laura never remarried.

Grace was born while Laura worked her second homestead near Palisade, Hayes County, Nebraska more than ten years after moving to that state. We have no clues in our family papers for the identity of Grace’s father. We know only of these associates of Laura:

- George Edmonds. Perhaps Laura reconnected with him at some point, either if he traveled through Nebraska or she returned home to Michigan for a visit.

- Robert Mickey and Wm. Hyatt. These men witnessed Laura’s intent to make proof of her claim for her first homestead near McCook, Red Willow County, Nebraska in June, 1885.

- William F. Smith and John Lane (Layne). These men also witnessed her intent to make proof, and they subsequently executed affidavits in support of her homestead claim in August, 1885.

- Cyrus “Si” Smith. Laura worked at his wagon and harness shop in Palisade, Nebraska. He executed an affidavit in support of her Palisade homestead in 1898.

- Richard Ryan. He also executed an affidavit on her behalf in 1898.

- Leslie Lawton. By 1904, Laura knew this Civil War veteran, and she also worked for him near Palisade. He was instrumental in encouraging her to relocate from Palisade to Haigler, Dundy County, Nebraska to take up a larger homestead. They lived together for a time while Lawton was separated from his wife.

- Clyde Cole. This son-in-law of Leslie Lawton homesteaded on a place adjacent to Laura’s in Dundy County. In later years, he served as guardian to her son Joseph Edmonds.

- Wm. Palmer and C. F. Fay. These men served as witnesses for Laura’s intent to make proof of her Dundy County homestead in 1911.

- B. H. Bush, and W. J. Hacker. These men signed affidavits in support of Laura’s Dundy County homestead application in 1912.

Would any of these men be a likely candidate for my great-grandfather? Someone fathered Laura’s little girl at the end of 1895, but she did not disclose that information to her daughter.

I think the only way we will ever learn his identity is through a DNA match. My father has taken a couple of autosomal DNA tests, and he inherited 25% of his DNA from our mystery man. Perhaps we can uncover a match if another descendant of my great-grandfather ever takes such a test.

Traveling the Way My Ancestors Did

For some time, my husband/tech advisor and I have pondered traveling by train. We took a half-day trip many years ago, and we kept thinking we might enjoy a longer rail journey. Last week we had the opportunity to try it when he needed to attend a conference in San Francisco. We seized the chance to take the train to get where we needed to go, the same way our ancestors used to do.

For some time, my husband/tech advisor and I have pondered traveling by train. We took a half-day trip many years ago, and we kept thinking we might enjoy a longer rail journey. Last week we had the opportunity to try it when he needed to attend a conference in San Francisco. We seized the chance to take the train to get where we needed to go, the same way our ancestors used to do.

We caught Amtrak’s California Zephyr at Union Station in Denver. This line runs daily from Chicago to San Francisco. They say it offers one of the most beautiful rides in North America. We loved the scenery during our two-day trip. Highlights included the Rocky Mountains, the Moffatt Tunnel, scenic canyons, and Donner Pass.

We also loved the pace of train travel. We had a roomette with large, comfortable seats, a table, and big windows. As we rolled along, we relaxed and caught up on reading, napping and conversation.

The train served three tasty meals a day in the dining car. There we had the opportunity to share a meal with fellow travelers. At night, a steward converted our seats into upper and lower bunk beds.

During our trip, I found myself thinking about my forebears who had traveled on the train to new homes. The Bentsen ancestors caught the train to Culbertson, Montana after traveling across the ocean from Norway. My great-grandmother Laura Riddle went by train from Michigan to Nebraska when she began her life as a homesteader. For them, train travel represented the state-of-the-art mode of transportation.

In the mid-twentieth century, my grandmother Grace Reed preferred train travel for her journeys. She took her young children on the train to visit her family. In later years, she traveled from Colorado to Wyoming to visit her grandchildren. I remember her disappointment when the railroad discontinued passenger service on that route in the 1960’s. After that, she took the bus for her visits, but she really missed the comfort of the train.

On our own trip, we learned that we like train travel. Others seem to like it, too. Several of the passengers on our trip spoke of their goals to take all the rail lines in the United States as a way to see the country. Next time we need to travel somewhere, I think we would consider booking another train trip.

We Reluctantly Fill In a Death Date

This week our family experienced the sad side of genealogy. Our three-year-old granddaughter lost her other grandmother to pneumonia, and we regretfully must complete Sharon’s death date space on our family group sheets.

This week our family experienced the sad side of genealogy. Our three-year-old granddaughter lost her other grandmother to pneumonia, and we regretfully must complete Sharon’s death date space on our family group sheets.

Our granddaughter knows that her grandma has died, but she does not understand what that means, nor does she appreciate the finality of it. This little girl does not fully understand that she will not see her grandma again.

Sharon was a wonderful grandmother who spent countless hours with her grandchildren, taking them to school and soccer practice, cutting their hair, and encouraging them to root wildly for the Denver Broncos. But she will not be there for our mutual granddaughter’s soccer games and school performances. Nor will she be there for the new little granddaughter due to arrive any day now.

Sharon won’t be buying any more Bronco cheerleader outfits and championship T shirts for her granddaughters. She won’t be re-creating her beautiful back yard where they have played every summer. She won’t be hosting any more holiday dinners for them.

It is a sad week for all of us, and our little granddaughter has lost her grandma all too soon.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 8—Anna Petronellia Sherman (1865-1961)

Anna Petronellia Sherman lived a very long life. According to death certificate information provided by her son Thomas Aaron Reed, she was born on April 1, 1865 to Thomas Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh and died in Clinton, Missouri in 1961 at the age of 95. Contrary to the information on her death certificate, she was probably born in Indiana. No record of her mother has been found, and family lore claims that she died in Indiana before 1870. The mother was reportedly from Germany or Holland, making little Petronellia either half German or half Dutch.

Anna Petronellia Sherman lived a very long life. According to death certificate information provided by her son Thomas Aaron Reed, she was born on April 1, 1865 to Thomas Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh and died in Clinton, Missouri in 1961 at the age of 95. Contrary to the information on her death certificate, she was probably born in Indiana. No record of her mother has been found, and family lore claims that she died in Indiana before 1870. The mother was reportedly from Germany or Holland, making little Petronellia either half German or half Dutch.

The motherless girl strongly disapproved when her father remarried 19-year-old Alice Farris in 1881. Ironic then, that two years later on September 6, 1883 Petronellia herself, at the age of 18, married an older widower, 38-year-old Samuel Harvey Reed, in Coles County, Illinois. She became the stepmother to his two daughters, Annie and Clara. He called her “Pet” and drove her around in a buggy while she held a fancy parasol. She later said she was attracted to his big, white house (which actually belonged to his father) and to the highly-respected Reed name. The Reeds, in turn, hardly approved of Samuel marrying the daughter of a poor blacksmith who drank, especially when Samuel’s first wife had been very well off. Samuel immediately moved his new bride to Kansas and later, to Missouri. They had seven children: Bertha Evaline (1884), Caleb Logan (1887), Viola May (1889), Robert Morton (1891), Samuel Carter (1892), Thomas Aaron (1894), and Owen Herbert (1896 or 1897).

People who knew Petronellia have described her as temperamental, religious, and hard-working. Sometimes she kept a perfect house; at others she allowed chickens indoors. One time she chopped down all the trees in her yard because the songbirds annoyed her early in the morning. She had a fiery temper and could not get along with others. She and Samuel divorced in 1904.

She joined the No. 1 Methodist Church in Mountain Grove, Missouri when she was 23 and remained a member for the next 73 years. She read the Bible completely more than 20 times, played the church organ, and taught Sunday School until she was in her 90’s. She lived a simple, frugal life without an indoor toilet. If her children tried to give her money, she would donate it to Boy’s Town in Nebraska.

Petronellia worked for the Post Office off and on. She met Samuel Reed while working at the Charleston, Illinois post office. She was the first Postmaster at Graff, Missouri, serving from 1895 to 1899.

After her divorce from Samuel Reed, she married Captain James W. Coffey, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War, in 1906 in Texas County, Missouri. Some of her sons worked on Coffey’s farm. The marriage lasted only a few years and ended in divorce. With her children grown and no husband, Petronellia needed to earn a living.

She resumed the Reed surname and decided to apply for a homestead. Selling a proved-up homestead was a good way for single women to build a nest egg. To do so, she needed to move to a public-land state with homesteads available.

Several of her younger children had relocated to the Nebraska-Wyoming area, and her son Robert Morton Reed was the railroad station agent at Farthing, Wyoming, near Iron Mountain in Laramie County northwest of Cheyenne. Petronellia joined him there and took up a stock-raising homestead in 1918. She raised chickens and a few head of cattle, and she tried to grow some crops, without much success. One year, she harvested only a bucketful of potatoes. She became a crack-shot antelope hunter to survive.

By the end of her five-year homestead term, her son’s family had moved on to Wheatland, Wyoming with his railroad job. Petronellia hated the cold, windy, treeless prairie, so she sold her homestead and moved alone back to Missouri. Her homestead is now part of the large Farthing Ranch.

She lived out the rest of her long life in Mountain Grove, Missouri, growing blind in old age and eventually moving into a nursing home the last year of her life. She is buried in the churchyard of the No. 1 Methodist Church. She lies next to the grave of her daughter Bertha’s unnamed stillborn daughter who had been laid to rest there over 50 years earlier, in 1909.

Genealogical Clean-up

I keep several stackable trays on the credenza near my desk. I have each one labeled with one of my family surnames. As I come across documents pertaining to a surname, I make a copy and toss it into the appropriate tray.

I keep several stackable trays on the credenza near my desk. I have each one labeled with one of my family surnames. As I come across documents pertaining to a surname, I make a copy and toss it into the appropriate tray.

If I kept digital copies of these items, I never would think to go back and look at them. But with paper copies staring me in the face, I remember to go through the bin whenever I am working on a surname. This week I pawed through the Sherman tray.

I found several things in there that I had forgotten I had:

- Thomas and Anderson Sherman’s 1863 Civil War draft registration record from Johnson County, Indiana.

- Evaline Sherman Alvey’s Civil War widow’s pension index card.

- Thomas Sherman’s listing as a taxpayer in Edgar County, Illinois in 1878, and as a blacksmith in Loxa, Illinois in 1895.

- Sherman death listings in various places where Thomas lived, including Johnson County, Indiana and Coles County, Illinois. Can these people be relatives of his?

All of these documents shed light on the life of my great-great grandfather, Thomas Sherman. I need to analyze them for all the information I can glean. Hopefully they will help me focus my next research steps. I feel like there is so much more to discover about Thomas.

He did not leave many footprints in the historical record. Once I pull everything out of the Sherman bin that pertains to him, I can fashion a research plan that will enable me to learn more about his life.

The Shermans and the Draft

Nearly one hundred years ago the young men of America marched off to register for the World War I draft. I looked at some of those registration cards this week. There I found Charles, George, Claude, and Walter, the four sons of my great-great grandfather Thomas Sherman. I learned several things about them:

Nearly one hundred years ago the young men of America marched off to register for the World War I draft. I looked at some of those registration cards this week. There I found Charles, George, Claude, and Walter, the four sons of my great-great grandfather Thomas Sherman. I learned several things about them:

- Birthplaces. Interestingly, the draft boards did not use the same registration form every year. The forms filled out by the younger sons, Claude and Walter, in 1917 asked for birthplace. The forms filled out a year later by the older sons, Charles and George, did not. From census records I know that Charles was born in Missouri, but I wish the draft card had given an exact location. The other boys were all born in Illinois, and now I know that Walter was born at Janesville, Illinois. Claude’s card says he was born at Johnstown, Illinois. I am unfamiliar with this location and did not know that the father Thomas Sherman had ever lived there. I need to do some more investigating of this clue.

- Residence. When they registered, George and Claude lived in Charleston, Illinois, as I expected. Walter lived nearby in Bushton. Charles resided in Dexter, Missouri. He had left Illinois that year at the request of the Coles County Overseer of the Poor after having lived hand to mouth on the county dole for many months. Charles was quite the black sheep.

- Occupations. The Shermans were blacksmiths, and all but the youngest son Walter pursued this trade during World War I. Walter worked at a grain elevator.

- Physical Descriptions. All the sons but George were described as slender. The older boys, Charles and George, were of medium height; the younger sons were tall. They all had dark hair. Only Walter had blue eyes while the others had brown. Does my dad look like any of them? He was tall, slender, blue-eyed, and had dark hair.

- Claude and Walter claimed exemptions from the draft on the grounds of being needed to support dependents. The form did not name these people, but the list included Walter’s mother.

These draft cards gave me a good look at family members from another era. You can find the records on Ancestry.com.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks No 7: Samuel Harvey Reed (1845-1928)

Some people live in one place all their lives. A few even stay in the same house. They spend a lifetime in familiar surroundings with their families and longtime friends and neighbors. Samuel Harvey Reed was not one of those people. He had “that Reed wanderlust” and always felt drawn to a new opportunity in another Western state.

Early Life

Sam was born on April 9, 1845 in Ashmore Township, Coles County, Illinois, the firstborn of Joseph Caleb Reed and Janete (aka Jane) Carter. Both the Reed and the Carter families had traveled from Kentucky to become pioneer settlers in the Ashmore area around 1830. When Sam was born fifteen years later, the area remained very rural. As he grew up, ten-year-old Sam would have seen the 1855 construction of the Coles County Poor Farm in the township. The village of Ashmore would not be incorporated until after the Civil War in 1867.

Young Sam worked as a laborer on his father’s farm. Both his mother and father came from large families, so in addition to his own ten siblings, he had many cousins nearby. His mother had joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church a few years before he was born, and that is where he likely attended services. He learned to read and write at the local grammar school.

Whether or not Sam served in the Civil War remains the unresolved question of his young adulthood. He was certainly the right age for enlistment, turning 18 in 1863. Some of his relatives saw military service. His cousin Nancy Reed Ashmore’s husband, Hezekiah Ashmore, served the Union as a lieutenant in the 123rd Illinois Infantry. Two of his Boyd cousins served in the 8th Illinois, and both died in the War. Robert died from wounds received at Ft. Donelson, and George died at Vicksburg.

Did Sam enlist, too? Unlike Hezekiah Ashmore and the Boyd brothers, most men who served from Coles County came from the western side of the county. Settlers on the eastern side, like the Reeds, had migrated from Kentucky. They harbored southern sympathies and hated abolitionists even though they personally had not owned slaves. They opposed the draft and avoided the Army.

No record of military service for Sam has been found. The National Archives has no service file, nor did Sam ever file for a pension based on military service. No record of his membership in the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans, has been found. His name does not appear on the list of service men from Coles County or on the roster of any Illinois unit. Interestingly, neither does the name of his cousin Caleb Robertson Reed who was also said to have served. Searches have not been done for his remaining Reed and Carter cousins.

Could Sam have served from another state? Perhaps, although he resided on his father’s Illinois farm both before and after the war. It is possible, though, that he went away to enlist and then returned when he completed his service.

Despite the lack of proof, Sam and his family always claimed that he did fight for the Union. His daughter Bertha remembered that he would carry the flag while marching in parades with the Grand Army of the Republic. The family also offered service information whenever the question appeared on a census enumeration. The 1885 census for Edwards County, Kansas states that he enlisted in Illinois and served on pontoons. The 1890 Special Schedule of Surviving Soldiers for Texas Co., MO, reports that he served from April 9 – November 4, 1864 as a Private in Co. H, 8th Kansas Infantry, yet his name does not appear on this unit roster. The 1910 U.S. census for Grant County, Nebraska indicates simply that he served in the Union Army.

Family lore offers an unconvincing explanation for the lack of service documentation. They say that while returning home from the Civil War, Sam’s boat capsized. He was saved, but he lost all of his papers. The boat accident may be a true story, but why would Samuel have been carrying the only existing proof of his enlistment? There would have been official records kept elsewhere.

So did he serve? We have only his word that he did.

Marriage to Nancy Jane Dudley

A few years after the war, Sam married his neighbor Nancy Jane Dudley, daughter of Guilford Dudley and Mary Wiley, on August 1, 1869 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. Sam’s younger sister Emma Jane also married into the Dudley family a few years later.

This close connection to the prominent Dudleys thrilled the Reeds. The Dudleys descended from Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favorite of Queen Elizabeth I of England. The family also counted Sir Thomas Dudley, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, among their ancestors. A group of three Dudley brothers, including Nancy’s father, had been the first white people to settle in the Ashmore area of Illinois. They founded a now-defunct town called Bachelorsville where Guilford Dudley ran a store. Indians often traded at his store.

After their marriage, Sam and Nancy moved west to Centerville Township, Neosho County, Kansas. The Osage Indians had recently ceded the area, and settlers flocked in. The family of author Laura Ingalls Wilder settled a few miles away at the same time. Unfortunately, Charles Ingalls chose land that had not been ceded, and the government evicted him as a squatter some months later. Sam did not make that mistake.

For unknown reasons, the Reeds did not stay long in Kansas, either. They farmed that summer of 1870, and their first child, Anna Reed, was born there on August 23. Later in the year, they made arrangements to sell out and return to Illinois. Perhaps Nancy could not cope with homesteading life after Anna’s birth and needed to return to her family. When she died 10 years later, her death record stated that she had suffered from anemia for a decade.

By 1872, the Reeds had settled again in Illinois. Sam witnessed the will of his cousin Mary E. Reed on April 12, 1872 at Ashmore. Nancy delivered a second daughter, Amy, on July 13 the same year. A third daughter, Clara, was born at Bachelorsville on July 8, 1875.

Three months later, on September 21, 1875, little Amy Reed passed away at the age of 3. Her death was not recorded in the county record, so her cause of death remains unknown. That year Nancy and the other heirs of Guilford Dudley had donated land southwest of Ashmore to create a cemetery adjacent to the Enon Baptist Church. Amy was buried on these grounds.

Sam and Nancy continued to live in the Ashmore area although not always in Coles County. In 1879 they resided in Douglas County, just north of Coles. By the next year, they had returned to Ashmore, and Nancy was pregnant again. On July 2, the census taker visited their house and listed the Reed household members as Sam, Nancy, Anna, and Clara.

The next day, July 3, 1880, a fourth daughter, Mary Jane, was born. Nancy died in childbirth. Sources conflict on whether Mary Jane died the same day or lived for up to a month. Mother and daughter were buried alongside Amy Reed in the Enon Cemetery.

Marriage to Anna Petronellia Sherman

Suddenly, Sam Reed found himself a widower with two daughters, ages 10 and 5. He must have turned to his family for some help over the following months, but he needed a wife. He noticed a young woman working in the Post Office. She was Anna Petronellia Sherman, daughter of Thomas Lane Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh/Stillenbaugh [Stillabower/Stilgenbauer?].

They married on September 6, 1883 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. She was 18, he was 38, and his family was dismayed to see him wed the daughter of a poor, alcoholic blacksmith. But Sam delighted in his pert, young wife. As she carried a parasol against the sun, he drove her around in a carriage and called her “Pet”.

Then once again, Sam took his bride to Kansas. On August 31, 1884, his fifth daughter, Bertha Eveline, was born in Harper County. By mid-1885 the family, consisting of Sam, Petronellia, Clara, and Bertha, had moved on to Franklin Twp., Edwards County, Kansas. Presumably, 14-year-old Anna remained in Illinois with her grandparents.

Yet again, Sam did not stay long in Kansas. He soon relocated to Missouri where he raised hogs and a few cattle. There, on October 20, 1887, his first son and sixth child, Caleb Logan, was born in Upton Township, Texas County, Missouri. As was family tradition, the boy was known by his middle name “Logan”, and he was followed by Viola Mae on April 20, 1889, Robert Morton “Mort” on March 14, 1891, Samuel Carter “Cart” on October 2, 1892, Thomas Aaron “Aaron” on September 17, 1894, and Owen Herbert “Herb” on December 6, 1896.

Sam and his family have not been found on the 1900 U.S. census although they continued to live in Missouri through the 1890’s. Clara had gone to nursing school there and then married Gwinn Routledge at Rolla in 1898. Petronellia was postmaster at Graff from 1895-1899. But the Reed marriage was in decline, and we have no record proving that Sam remained with his family during these years. After all, he was increasingly a wanderer.

On May 26, 1904 he and Petronellia divorced at Houston, Texas County, Missouri. Petronellia asked for custody of all her children including Bertha, who had married Charles Richards in Oklahoma earlier that year. The court required Sam to pay his wife alimony in the sum of eighty dollars cash and to convey his 200-acre farm in Texas County to her. He also had to pay her legal fees and cancel her $150 debt to him. In return, Petronellia released her dower right to Sam’s Wright County farm.

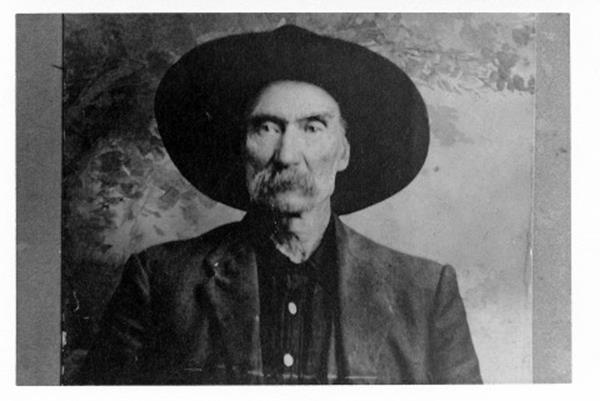

Samuel, the Wanderer

After that, Sam seems to have taken off on a 20-year itinerant life. Even his appearance changed. He had previously worn a full beard, but now he shaved off most of his whiskers to leave only a mustache.

By 1910 he worked on a western Nebraska ranch owned by a kindly woman named Theodocia Evert. She was a widow whose own family was grown but who was raising her sister’s teenage daughter, Grace Riddle. That summer, Sam’s son-in-law Charles Richards joined him on the ranch work crew. In a horrifying haying accident, Charles lost his legs. Bertha and their two children traveled from Missouri to Nebraska to nurse him back to health. The Richards marriage, already troubled, did not survive this tragedy, and they subsequently divorced. Bertha later married Theodocia Evert’s son Henry and remained in Nebraska for the rest of her life.

It is unclear how long Sam remained in Nebraska, but several of his children settled there in the years before World War I. Cart and Aaron homesteaded in Cherry County. Herbert took a turn working on the Evert ranch and married Grace Riddle. Viola lived nearby for a while and married Bert Gwinn at Alliance in 1919. She, Cart, and Aaron all served in World War I from Nebraska.

After his stint in Nebraska, Sam spent some time in Oklahoma. Oil had been discovered there, and Sam looked to invest. When his parents died in 1903 and 1907, he did not want the Illinois farm and inherited money instead. Mort’s children remembered that despite Sam’s high hopes, the oil play did not go well. Complicating the situation, Sam had become involved with a woman and then suspected her of wanting only his land and money. It is unclear whether or not he had married her. Mort finally travelled to Oklahoma to help resolve matters for his father. After this incident, Sam’s whereabouts are unknown, and he has not been positively identified on the 1920 U.S. census.

Later, after living in the western states for nearly 40 years, Sam returned to his home town when he was in his mid-seventies. In 1922 he began living with his eldest daughter Anna McDavitt and her family about 2 miles east of Ashmore, Illinois. Sometimes he experienced anxiety attacks and the urge to “go somewhere”. Other than that, he was in generally fair health although he had circulation problems and an enlarged prostate.

By 1927 he displayed more symptoms of age-related mental decline. He became increasingly wild and destructive around the house and did not keep himself clean. He suffered from hallucinations and chattered nervously about imaginary events. After an especially severe attack that required sedation, Anna realized she could no longer keep him at home. She had him declared incompetent, and committed him to the Jacksonville State Hospital for the Insane. There he died in his sleep a month later on October 2, 1928 at the age of eighty-three.

His body was returned to Ashmore for burial. His grandson Joseph VanMeter McDavitt (“Van”) earned $5 for cleaning up and readying the burial plot. After a funeral at the Baptist church with a Presbyterian minister officiating, Samuel was laid to rest in the Enon Cemetery next to his first wife Nancy and their daughters Amy and Mary Jane.

Sam’s estate consisted only of some money in the Ashmore bank. He had not led an industrious life, and most of his inheritance had been lost in poor land deals. After payment of his final expenses, $549.81 remained. Distribution to his nine surviving children amounted to $61.09 each, but Viola and Mort refused to accept their shares. They directed that their inheritance should go to Anna to compensate her for caring for their father.

Although Samuel did not leave large sums to his children, he did give them some valuable advice. They all remembered that he often said, “You inherited a good name, now keep it that way.” He may have wandered about and squandered his money, but he always kept what he valued most, his good name.

Two Girls Named Clara

My Sherman family lived in Illinois in the early twentieth century. Luckily for me, I can read the local Mattoon newspapers online to learn about them. I have searched for most of the Sherman names in my database, and this week stories of two of my grandfather’s cousins turned up:

- Clara Sherman (1908-1926). The daughter of Charles Sherman, this young woman married Howard Cook at the age of fourteen. She suffered from tuberculosis, died at seventeen, and left behind a 5-month-old daughter. Members of the Spiritualist Society conducted her funeral service at her maternal grandparents’ home.

- Clara Gladys McNamer (1905-1974). This Clara was the daughter of Ethel Sherman and Edward McNamer. One Sunday night in December, 1921 when Clara was 16, a local boy named Forrest Stoner arrived in his car to take her to a church meeting. They did not return that evening, and her parents notified the authorities. An all-night search commenced, but no one could find them. The next morning, the County Clerk in a neighboring county called to let someone know that the couple had eloped and married that morning.

I do not think my grandfather ever met these cousins. His family lived in the Missouri Ozarks. The families did not seem to keep in touch. The girls were the  daughters of my great-grandmother Petronellia Sherman’s half-siblings, and she had not approved of her father’s re-marriage.

daughters of my great-grandmother Petronellia Sherman’s half-siblings, and she had not approved of her father’s re-marriage.

After these families lost touch with one another, we knew nothing of those cousins who had a close blood tie with us. The newspapers have helped me again to know these people a little better.

Back To The Newspapers

I have mentioned before that I have found a great deal of late 19th century and early 20th century family information in local newspapers.

I have mentioned before that I have found a great deal of late 19th century and early 20th century family information in local newspapers.

I spent this week researching the life of one of my great-grandmother Anna Petronellia Sherman’s half-brothers. He can only be described as a black sheep. The newspaper repeatedly carried stories of his exploits including excessive drinking, wife-beating, womanizing, on-the-job injuries, and a divorce.

This man must have caused a lot of heartache to his family. I can only imagine the damage he inflicted on the lives of his four children. All this hard living finally caught up to him when he died in 1933 at the age of fifty-one.

Anna’s own father was said to have drunk to excess as well—a family trait? Anna herself did not imbibe as far as I know. In fact, she married young and left the state, never to return. Perhaps she had had enough.

I still have the remaining half-siblings to learn about, and I wonder if they all had trouble coping with life the way their father did. Most of them lived in the same small town, so I will be combing those newspapers again to learn more.

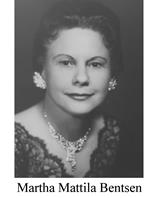

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 6—Martha Louise Mattila (1906-1977)

My maternal grandmother Martha had a multicultural upbringing. Her parents Alexander and Ada had immigrated from Viipuri, Finland in 1905, the year before she was born. They settled on the Iron Range of Minnesota, near Hibbing. Martha was their first child, and they spoke Finnish at home.

My maternal grandmother Martha had a multicultural upbringing. Her parents Alexander and Ada had immigrated from Viipuri, Finland in 1905, the year before she was born. They settled on the Iron Range of Minnesota, near Hibbing. Martha was their first child, and they spoke Finnish at home.

At that time, Hibbing was still getting settled after its founding in 1892. The mining companies heavily recruited in eastern and southern Europe to find workers. Martha grew up among various ethnic groups including Poles, Bohemians, and Italians. She also had an extended Finnish family nearby, because three of her father’s sisters immigrated, too. She met her life-long friend Melia when she started school.

Martha’s own family attended the Lutheran Church, but many of the neighbors were Roman Catholic. She spoke of the time when she was about five years old, and she heard a Catholic bishop was coming to town. There must have been some anxious preparation in the community for this occasion because Martha was so afraid that she hid under the bed. “And I wasn’t even Catholic,” she laughed later.

Martha spent her early years believing she would be an only child. Not until she was 10 did another sister, Aida, arrive in 1916. Two brothers followed: Hugo in 1918, and Peter in 1919. Martha suddenly found herself in the role of mother’s helper.

She was a smart girl, and despite her household duties, she finished high school early. She went on to college at the Duluth branch of the University of Minnesota. There she earned a two-year certificate in elementary education. Martha became a teacher.

She sought adventure and applied for a job far away in Montana. With her ability to mingle easily among other ethnic groups, she was hired to teach in a Norwegian community near Redstone, Montana. She taught at a one-room schoolhouse and lived with local farm families.

On 2 June 1928 she married Bjarne Bentsen, the older brother of two of her students, Jennie and Otto. For a year or so, until the birth of their daughter Joyce, Martha and Bjarne stayed in Montana. Sometime in 1929 they decided to relocate to Martha’s hometown, Hibbing.

They settled into a house that her father had built, right next door to her parents and younger siblings. Martha focused on raising Joyce and eventually had two more children, a son Ronald (“Sonny”) and another daughter. She had a somewhat fractious relationship with her mother but also enjoyed gossiping with her in their native Finnish language. Her children felt as much at home in their grandparents’ house as they did in their own.

The family remained in Hibbing, except for a short-lived move to a larger house, until Martha’s parents had both died. Then Bjarne got the itch to return to the West. He hoped to become an electrician to capitalize on the post-War building boom.

They uprooted their family and drove to Wyoming. Bjarne worked as an electrician here and there for the next few years while Martha supplemented the family income by teaching school. They finally landed in Rapid City, South Dakota, where he set up an electrical shop. Their youngest child graduated from high school and got married. But these happy events could not outweigh the stress of constant moves and uncertain income. Their marriage fell apart.

Bjarne and Martha divorced in 1960, and Martha remained in their little house. At first she enjoyed life by socializing with the neighbors and participating in veteran’s groups. She served as President of local chapters of both the VFW Auxiliary and the American Legion Auxiliary. Martha loved to dance and faithfully attended the weekly dances at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City. She really liked dancing with all the young airmen.

Bjarne and Martha divorced in 1960, and Martha remained in their little house. At first she enjoyed life by socializing with the neighbors and participating in veteran’s groups. She served as President of local chapters of both the VFW Auxiliary and the American Legion Auxiliary. Martha loved to dance and faithfully attended the weekly dances at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City. She really liked dancing with all the young airmen.

Yet her carefree life as a divorcee did not last long. Bjarne was not good at paying his alimony, so Martha continually scrambled for money. For a few semesters, she offered room and board to students from the South Dakota School of Mines. She continued to teach school off and on, first at the Bergquist School in Rapid City. After the school district began requiring teachers to have a 4-year degree, she began commuting to teach at the rural Fairburn school where her 2-year diploma still sufficed.

When it came time to collect Social Security, she found she did not have enough work credits to qualify. Martha found a job in a local bakery where she worked until she could receive benefits.

Eventually the time came when she needed to sell her house. The upkeep had become strenuous, and she wanted to unlock the equity in the home. She hated leaving the neighborhood she had known for over twenty years, but she made friends quickly in her new apartment complex.

She lived there until 1977 when her health began to fail. Her daughter Joyce took Martha into her home in Casper, Wyoming. After a short time, it became apparent that Martha needed a nursing home. She hated it there and lasted only three months. On the 26th of August 1977 (Bjarne’s birthday) she passed away after a stroke.

Martha was not particularly religious, and she did not have a church funeral. The family held a simple memorial service for her in a funeral home chapel. She was buried in the Highland Cemetery in Casper.

Martha liked pretty things, and she did beautiful crochet work. Her family still has her china, silver service, and many afghans and doilies that she made.