Archive for the ‘52 Ancestors’ Category

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 15—Caleb Reed (1818-1903)

A large extended family of Reeds began with the birth of a baby boy near a small Kentucky stream on 1 December 1818. At a farm along a waterway called Elk Creek southeast of Louisville, Kentucky, Caleb Reed came into the world that day.

The Elk Creek area was part of Shelby County at the time, but the state later split off lands from Shelby, Nelson, and Bullitt Counties to form the new Spencer County a few years later in 1824. Thus, we find Reed records in two Kentucky jurisdictions even though the family did not move.

At the time of their son’s birth, parents Thomas Reed and Ann Kirkham Reed already had three other children, Robertson (b. 1808), Eliza (b. 1810), and Jane (b. 1817). The family later added another brother, William (b. 1822).

Baby Caleb became one of many family members to share the same name. His paternal grandfather was also named Caleb Reed. That Caleb had a son Caleb C. Reed (our Caleb’s uncle). Our Caleb later had a nephew, Caleb R., son of his brother Robertson. Subsequent generations would continue to use the name. Our Caleb would have two grandsons who shared his name: Caleb Logan Reed and Caleb Reed Wright.

Some uncertainty surrounds Caleb’s full name. The family Bible simply gives his name as Caleb with no middle name. His marriage record lists his name as Caleb Samuel Reed. A different name appeared in his obituary where the informant reported his name as Joseph Caleb. Neither of these full names is corroborated by any other source.

Caleb lived his first decade in Kentucky until his parents decided in 1829 to move to lands newly-opened for settlement in Illinois. On his eleventh birthday the family left the state of Kentucky to find a new home in the wilderness. The journey consumed nearly a month.

Arriving in Edgar County, Illinois, they spent a few days. About New Year 1830, they went westward on to Coles County. They settled about one and a half miles from of the village of Ashmore. Caleb Reed later owned that farm.

At some time during his life, Caleb learned to read and write. If he attended school in Illinois, perhaps he went to the first school in Ashmore, located at the southwest edge of town. It was a fair weather school made of logs and had an earthen floor. The three sided structure opened to the south with a split log shelf along the two sides. The seats were crude split logs with pegged legs. The building also served as a church.

When Caleb was 25 years old, he married a neighbor girl, Jane Carter, daughter of John Carter and Mary (Polly) Templeton Carter. Caleb and Jane wed on 22 February 1844 at Coles County, Illinois where they were united by a Justice of the Peace. They eventually had eleven children: Samuel (1845-1928), Mary (1847-1855), Martha (1849-1918), George (1851-1886), Thomas B. (1853-1854), Emma Jane (1855-1888), John (1857-1921), Thomas L. (1860-1925), James (1862-1864), Ida May (1864-1954), and Albert (1866-1890).

Even before Caleb married Jane, he began accumulating land holdings. At the age of twenty-two he went to the federal land office at Palestine, Illinois on 20 May 1841 and bought the SESE/4 of Section 6, T12 N, R14W, Coles County, Illinois. He received an adjacent 177 acres of land in Section 6 from his father in 1847. On 1 February 1850 he bought the NESE/4 of the same section. At the time of the 1850 United States census, their nearest post office was in Hitesville, a town about 2 miles southeast of Ashmore. It no longer exists.

Caleb’s younger brother William died in 1845, and his death left four surviving Reed siblings. When their father Thomas passed away a few years later in 1852, Caleb inherited a 1/4 share of the family farm. He and his brother Rob then purchased their sisters’ shares. Caleb settled in to life as a farmer and stock raiser. He never sought official positions because he felt his farm of 430 acres required his entire attention. He and Jane lived on the site of his father’s original settlement.

By 1860, Caleb owned $1200 worth of livestock. He was a farmer with $6000 in real estate and $1000 in personal property. Today the farmland alone is worth over $3 million, and Caleb’s descendants still own it. In May and October 1864, when an income tax was briefly enacted to fund the Civil War, Caleb paid tax of $9 and $15 to the assessor.

The Masons organized in Coles County during the Civil War in 1863. Caleb Reed together with Jane’s brother-in-law Robert Boyd (her sister Nancy’s husband) became charter members of Ashmore Lodge, No. 390. Caleb was elected Junior Warden, and Boyd served as tiler or guardian to the entrance of the Lodge.

Coles County furnished more than its quota of soldiers for the Union Army during the war years, but most volunteers were from the western part of the county. On the eastern side, where the Reeds and Carters lived, there were many rebel sympathizers who had come from Kentucky. These people hated abolitionists and the draft. Although Caleb Reed did register for the draft as required in June 1863, there is no record of his eligible son Samuel registering or serving from Coles County.

As the war progressed, troops constantly moved through the Ashmore area. Local farmers supplied corn at the high war price of $.60 per bushel. Perhaps Caleb was able to add to his wealth by selling farm products to the Army.

As the war progressed, troops constantly moved through the Ashmore area. Local farmers supplied corn at the high war price of $.60 per bushel. Perhaps Caleb was able to add to his wealth by selling farm products to the Army.

In March 1864, Caleb and Jane must have watched with interest as tensions between Union soldiers and local insurgents known as Copperheads heightened in Coles County. On March 28, 1864, violence erupted when the former sheriff of Coles County and the Copperheads attacked a group of soldiers in Charleston, the county seat 10 miles from the Reed farm. In the end, 9 people died, 12 were wounded, and 29 men were arrested in what became known as the Charleston Riot. Among those apprehended was John Galbreath, a relative of Caleb’s sister Jane Reed Galbreath.

After the war, Caleb and Jane continued living on their farm. In 1878, Caleb was appointed by the Coles County Board of Supervisors to serve as a Grand juryman from Ashmore Township for the November term.

At some point, the Reeds decided to retire from the farm and move into Ashmore. They lived in one house for a while and then traded houses with their friend Newt Austin for a home located mid-block west of the Presbyterian Church. Newt was related to Jane’s sister Susan Carter Austin.

The Reed’s grandchildren visited often, and Jane would send them to the butcher shop to buy for the noon dinner. Some of the grandchildren complained about having to visit because they found nothing to do there. The only entertainment was to watch the trains come into town. The only reading material was the Sunday School newsletter.

By 1902, Caleb’s health was beginning to fail. He sold some of his land to his sons T. L. Reed and John C. Reed. The following year, he sold land in Section 7, Twp. 12 North, Range 14 West to his daughter Ida May Thompson for $1.00.

In the spring of 1903, the Mattoon, Illinois newspaper reported that Caleb Reed had taken quite sick on the previous Saturday, May 16, and remained in feeble condition. The following week he was no better. Ida Thompson visited her parents and then returned home to Indiana. Later that summer, she was again at the bedside of her aged father who was in very poor health.

On 10 November 1903 at his home in Ashmore, Caleb ate a hearty breakfast. He felt as well as usual but continued to be ill with kidney trouble. After his meal he went to take his customary rest while Jane was in another room attending to her household duties. Thinking that he had slept long enough she went to rouse him and found that he had passed away at the age of eighty-four.

Two days later on the day of Caleb’s funeral, the family sat at the house in an uncomfortable hush until it was time to go to Ashmore Cemetery. A few, including his widow, went by carriage, but the others walked behind the men carrying the casket. As one bearer tired, another stepped up to take his place. There was a graveside prayer.

Caleb left behind a large family clan that became known to later generations as the Reeds of Ashmore. Although he had outlived six of his eleven children, he had numerous descendants in Ashmore and beyond.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks nos. 13 and 14—Alex and Ada Mattila

Suomi, or “Finland” as most people know it, is a Nordic country east of the Bothnian Sea. Three ancient tribes settled there, the Finns, the Tavastians, and the Karelians. Even after Finnish unification under the Swedes, the eastern area known as Karelia retained an identity of its own. The people had long traditions of folk music and mysticism, and today the Karelian culture is perceived as the purist expression of true Finnic ways and beliefs. The Finnish epic poem, The

Kalevala, draws mostly from Karelian folklore and mythology. Many of the works of the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius took influence from The Kalevala.

Ada and Alex Mattila came from Viipuri, Finland, at the southern end of Karelian lands. This historically Lutheran province of Finland, known for its iconic Vyborg Castle, now lies divided between Finland and Russia in the area between the Baltic Sea and the White Sea. Over the centuries, the Swedes and the Russians have exerted a heavy influence over Karelia.

Beginning in the 13th century, these two fought bitterly over it, and a treaty in 1323 divided Karelia between them. The city of Viipuri (“Viborg” to the Swedes and “Vyborg” to the Russians) became the capital of the new Swedish province and ultimately the second-largest city in Finland. The surrounding area became part of Viipuri parish.

The Swedes retained control of Finland, including their part of Karelia, for the next 500 years until the Napoleonic Wars. In the meantime, the Russians maintained the remainder of the ethnic Karelian lands. After Napoleon, the Russians received Finland from the Swedes as part of the war settlement, and a unified Finland became a Duchy of the Russian empire. Thus the Karelians were reunited for the next hundred years under one ruler, the Czar.

Early Life

Into this troubled land and time, Alexander Mattila was born. His parents were Elisabeth (“Liisa”) Myllynen and Antti Abelsson Mattila. The father was listed as “Anders” in the official Swedish-language records of the time. “Antti” and “Anders” are the Finnish and Swedish renderings of the English name, Andrew.

The Mattilas lived in the rural village of Alasommes/Alasommee, Viipuri province, Duchy of Finland, and Alex was probably born at home. The actual date remains in question with various records reporting April or May, on the 8th or ninth of the month as his birth date. Some documents give the year as 1878, others say 1879. The Viipuri rural parish record lists his birth date as May 9, 1878 with his baptism following three days later on the twelfth of May.

Alex was the youngest of at least nine children, and he was the only boy. The father died when Alex was quite small, and his mother made her living by laying out the dead. The boy Alex often accompanied her.

As a young man in 1904, Alex worked and resided at Kolikkoinmaki, Finland. He planned to marry Ada Alina Lampinen, and marriage banns were published in January 1904 at the Lutheran church in Viipuri.

Fair-haired Ada was the daughter of Matti Lampinen, a lodger, and Anna Miettinen. Ada was born on September 25, 1879 in the village of Nunnanlahdentie, Kuopio Province, Finland, north of Viipuri. The area now lies in the province of Eastern Finland, created in 1997. On November 16, 1879, Ada was baptized in the Juuka parish. Ada’s children later said they knew nothing of her family.

Ada and Alex were married in Viipuri on May 14, 1904, and Ada transferred her church membership to the Viipuri rural parish in July. By 1905 Alex was working as a laborer in Viipuri. Conditions in Finland were hard at that time. Harsh Czarist rule left the Finns with little power over their own affairs. There were periodic famines, and tuberculosis afflicted many people.

Perhaps some of these problems led Alex and Ada to devise a plan to immigrate to America. Alex applied for and received a Finnish passport in February 1905. Leaving Ada behind temporarily, he traveled to the port town of Hanko on the south coast of Finland to catch a boat to Liverpool, England.

There he boarded the Cunard steamship Ivernia on March 25, 1905 bound for the United States. He arrived in Boston, Massachusetts on April 9, 1905. He reported to the authorities that he planned to join his “uncle” (actually his brother-in-law) Oskar Silberg in Superior, Wisconsin. Many Finns settled in the Great Lakes area where the climate resembled that of Finland, and industries needed workers.

Ada followed later, probably after Alex had set up a home for them. She applied for a Finnish passport in June 1905 but no passenger record for her has been found. She had certainly arrived in the U.S. by November 27, 1906 when their first child, Martha Louise, was born in Hibbing, Minnesota.

Building a Family in Minnesota

For the next several years, Alex worked to establish himself in the multi-ethnic Hibbing area. At least until 1915, he labored among other Finns and other men from all over Eastern Europe in one of the numerous iron mines of northern Minnesota. Meanwhile, he and Ada struggled to learn English. The U.S. census reports that Alex could speak English by 1910 but Ada and little Martha could not. A new language was easier for men to learn because they went out to work every day and heard it spoken there. When reading the 1920 census, one can almost hear their heavy Finnish accents. Their household is listed under the name Alex Sandermattila.

On March 6, 1915 Alex filed a Declaration of Intent to become a citizen of the United States. He was described as five feet, five-and-a-half inches tall, weighing 160 pounds, with a light complexion, medium brown hair, and brown eyes. The same description appears on his World War I draft registration card dated September 10, 1918. He became a citizen of the United States in 1922.

During the World War I years, Alex and Ada added more children to their family. These came as a surprise to their daughter Martha, ending her 10 years as an only child. Her sister, Aida Sylvia, arrived on October 2, 1916.

Aida lived the longest of the Mattila children, passing away at age 83 on June 18, 2000 after suffering a broken hip. She married twice, first to Walter Jametsky. They held their wedding reception at the Mattila house, and Alex Mattila’s older sister Anna Mattila Anderson attended. She was a staunch member of the Finnish Temperance Society, and when she found out that Alex was serving liquor to the guests upstairs, she got mad and went home.

Aida and Walter had one daughter, Judith Ann, and soon divorced. After the divorce, Aida and Judy lived with the Mattilas while Aida worked as a hotel elevator operator. Aida later married John Kerzie on May 23, 1953. They lived in Chisholm, Minnesota in the house where John was born. John worked in the mines and was active in labor union affairs. Aida kept house, putting her college training in home economics to good use.

A brother for Martha and Aida entered the household on June 5, 1918 with the birth of Hugo Alexander Mattila. Hugo had a wild streak and got into a bit of trouble as he grew. Once he went on a “bum” to California, hitching a ride on a train with a pal. The friend fell off and was killed. Another time, Hugo joined the cavalry, did not like it, and needed his mother to pay for his release. Along the way, he also worked as a ski jump instructor and boxed in Golden Gloves. Contrary to the advice of his temperance-minded aunt Anna, he enjoyed visiting local taverns. When he had too much to drink there, his policeman brother-in-law Bjarne Bentsen would take him home in the police paddy wagon.

Hugo eventually joined the Army Air Corps. During World War II, he served as a bombardier in Europe and achieved the rank of Lieutenant. While in the service, he married Ann Dorchock. During their marriage, Hugo went to college on the GI Bill and earned a degree in Civil Engineering. Meanwhile, he and Ann had three children: Robert Ray, Beverly, and Karen Marie. Sadly, little Karen passed away at the age of 6 in 1952 due to spinal meningitis.

Sometime after that, Hugo and Ann divorced, and Hugo remarried right away. He and Donna lived in Gainsville, Florida and had 6 children together: Kathleen, Virgina, James, Karen, Kelly, and Brian.

Hugo suffered a stroke later in life and was confined to a wheelchair. He died from the effects of a fire in his home on December 5, 1987 at the age of 69.

The last child and second son of Ada and Alex Mattila, Peter Bernhard, was born on November 19, 1919. Pete was not yet a teenager when Martha’s children Joyce and Ron were born, and he played with them as he grew up. He took them skiing (on barrel staves) and golfing (with homemade clubs while he worked at the local golf course).

Pete and Hugo would get wind-up toys for Ron for Christmas and then invite him over to play with them before Christmas. Later, both of the Mattila sons joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and lived in the camps.

Eventually, like his brother, Pete joined the Army Air Corps. He made it his career. His nephew Ron joined the Air Force, too, and during the Korean War they served near each other in Japan. According to Ron, Pete liked to get in bar fights when he was off duty. A few years later, on June 1, 1959, Pete died unexpectedly from a heart attack at age 39 while serving at Eglin Air Force base in Florida. The family later speculated that because Pete had never shown any signs of heart trouble, the Air Force was concealing his true cause of death.

A Carpenter’s Life

A Carpenter’s Life

By 1920, with his family of two daughters and two sons complete after 15 years in America, Alex Mattila had found some financial success. He owned a home without a mortgage on 2nd Avenue in Hibbing. He and his family lived on the ground floor, and they rented upstairs rooms out to two other families.

Finland is known for its carpentry industry, and somewhere along the way Alex learned this craft. By 1920 he had left the mines and was working as a carpenter. He continued in this occupation for the rest of his life, working at various times for the Messba Construction Company and the Ryan and Stavn Lumber Company where he worked at the time of his death. Years after he died, people in Hibbing would remember him walking down the street, carrying his carpenter’s toolbox. He built houses, but in his spare time, he enjoyed fashioning little hand-carved toys for his children and grandchildren. He also built a lovely dollhouse for his granddaughter, Sharon Bentsen.

As their finances improved, the Mattilas moved to a home Alex built on Thirteenth Avenue in Hibbing. They also purchased some farmland near the Hibbing airport. They hoped it would be valuable someday. Until they felt ready to sell it, they used the land to grow vegetables and other food. Ada often took the children and grandchildren out there to pick berries and mushrooms.

Alex sent his daughters to college in the 1920’s and 1930’s although only Martha actually graduated. She earned a 2-year degree allowing her to teach elementary school, and she promptly left Minnesota for adventure in Montana.

There she taught at the Two Tree country school near Redstone and lived with the Ole Bentsens, a nearby farm family. Their younger children, Jennie and Otto, attended the school. Martha married their older son, Bjarne, at the end of the school year on June 2, 1928.

Martha and Bjarne stayed in Montana long enough for their eldest child, Joyce Beverly, to be born on April 8, 1929 in Plentywood. After that, they relocated to Minnesota where they lived next door to the Mattilas, in another house that Alex had built. Not long after the move, Martha and Bjarne had a son, Ronald Duane, on January 14, 1931. Bjarne worked as an electrician in the mines for a while and then joined the Hibbing police force.

The Mattila’s seemed to enjoy having grandchildren next door. Ada always had a cake ready for snacking while they relaxed in the covered porch. She regularly offered them her homemade bread, which she would let rise on the stovetop before baking it in the coal stove. Alex liked to tease her that the big stove served double duty as her dressmaker’s model.

Alex and Ada also spent time teaching the ways of the old country to the children. Joyce used to accompany her grandmother to the local Finnish sauna and her grandfather on trips downtown. Ron helped his grandfather make dandelion wine. Both kids were amazed that neither grandparent celebrated birthdays, nor did their grandfather attend church. They did their own doctoring, including lancing boils and pulling bad teeth with the pliers.

They continued to speak Finnish at home, and Martha spoke with Ada in that language when she did not want the children to eavesdrop. Later, when Aida and Judy lived in the Mattila house during the 1940’s, Judy learned very little English before she started school. The teacher had to contact Aida to request that she work on English skills with the little girl.

Ada and Martha did not get along particularly well, and others sometimes had to settle their differences. Since they lived next door to one another, they shared a clothesline in the back yard. Ada valued tidiness, and she always collected her clothespins from the line when she took in her laundry. Martha preferred convenience and left her clothespins on the line until next time. Unfortunately, by then Ada had usually collected all of Martha’s clothespins and taken them inside. The battle of the clothespins escalated until Bjarne finally stepped in. He painted all of Martha’s clothespins red so there would be no confusion as to their ownership.

Aside from these typical family squabbles, life went along more or less as usual through the World War II years. The family avidly read letters from Hugo and Pete in the war zone, and the parents must have worried about them. We can wonder how they felt when their Viipuri homeland was ceded to the Soviet Union in 1944. Most of the Finns living anywhere near Viipuri walked out of the area and resettled in other parts of Finland. Russians moved in to fill the void, and very few Finns live in Vyborg and its environs today.

A Sorrowful Ending

In early April, 1945, Alex returned home from a trip downtown and reported in his accented English, “Roosevelt, he die.” No one believed him. Yet, it was true. Four-term President Franklin Roosevelt had passed away just as Alex had heard in town.

A day or two later, on a Saturday evening, Ada handed Alex his usual silver quarter to spend during an evening out. He always walked into town to gather with friends at a local tavern on Saturday nights. Several hours later, the police came to the Mattila door.

The family learned that while Alex walked home along the railroad tracks that night, he had been struck and killed by a train. Someone needed to go down to identify the body. The task fell to his son-in-law, Martha’s husband Bjarne.

No one was more stunned than Ada. She said, “I no live long now.” Yet she did live another three years. After her husband’s death, she finally joined the local Lutheran church, something Alex had never wanted to do. She also remained active in the Finnish Temperance Society and the Order of Runeberg, a Finnish cultural group.

One spring day three years later, on May 12, 1948 she went down the street to fetch her young granddaughter, Judy, who was out playing. While they walked back home together, Ada collapsed and died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 68. She was buried next to Alex in the Maple Hill Cemetery in Hibbing. Later, their son Peter was buried near them.

When she died, her estate was distributed according to a plan Alex had devised during the 1930’s. Aida received the house and its contents, Hugo received the money, and Peter received the farm. Martha, deemed “sufficiently provided for” by having already received an education and other forms of Alex’s goods , was disinherited.

, was disinherited.

That Alex and Ada had so much material wealth to leave behind is a tribute to their spirit. They had the courage and initiative to leave a bad situation to make a better life for themselves in a new land. They found a happy community of like-minded immigrants and thrived despite a language barrier, social stigma against immigrants, economic hardship during the Great Depression, and anxiety from two world wars. They gave their American-born children the tools they needed to succeed in life. They could be proud of what they had achieved.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks nos. 11 & 12—Ole Bentsen & Sofie Sivertsdatter

Between the years 1865 and 1930, an astonishing 780,000 Norwegians left Norway for the United States. Rapid population growth coupled with slow industrial growth in Norway left little opportunity for the young. Consequently, only Ireland with its potato famine contributed a greater share of its population to American immigration. Ole and Sofie Bentsen were among those who left in search of free land in America.

Between the years 1865 and 1930, an astonishing 780,000 Norwegians left Norway for the United States. Rapid population growth coupled with slow industrial growth in Norway left little opportunity for the young. Consequently, only Ireland with its potato famine contributed a greater share of its population to American immigration. Ole and Sofie Bentsen were among those who left in search of free land in America.

They came from the Land of the Midnight Sun where the sun neither sets in the summer nor rises in the winter. The Bentsens both hailed from the scenic Versterålen island group of Norway’s Lofoten archipelago in the Norwegian Sea. The main towns in this municipality, Andoy, Bø, Hadsel, Sortland, and Øksnes, sit on the narrow coast between mountain and fjord. Although far north of the Arctic Circle, the islands enjoy a maritime climate with mild winters. The Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, regularly offer a spectacular display to the people of Vesterålen. Perhaps this compensates some for the scarce winter daylight.

In this stark, treeless land, Ole Jorgen Lorentsen was born on September 6, 1880 at Bø to Lorents Nikolai (“Nick”) Anderson and Karen Marie Johansdatter. Norway did not require surnames at this time, but by the time Ole was born, the family had sometimes begun using the Bentsen (or Bentzen) name for everyone. Ole was baptized on December 12, 1880 at Bø parish. He grew up as the youngest child in the household with his parents and two older sisters, Lina and Riborg. Two foster children, Fresenius Pedersen and Riborg Hansdatter, also lived with them.

Vesterålen’s main industry is cod fishing supplemented with a little agriculture. By 1900, twenty-year-old Ole was one who made a living this way, sometimes spending two or three weeks at sea. According to the Norwegian census that year, Ole and Fresenius Pedersen worked as fishermen away from home at Aalesund, Norway.

Ole also served in the Norwegian military, as required by law, where he earned an award in marksmanship. During his service, he completed an assignment on the Arctic island of Spitsbergen, home of the fairy-tale Snow Queen. While he was there, he found two petrified leaves that he always regretted leaving behind. Today Spitsbergen houses the Global Seed Bank.

After leaving the service, Ole went to Stokmarknes to work. There he met Sofie Marie Sivertsdatter, daughter of Sivert Knudsen and Martha Karoline Dorthea Hansdatter. Ole and Sofie married on Easter Sunday, April 3, 1904 at Hadsel Church in Stokmarknes. Born July 3, 1878 at Valfjord and baptized on September 1, 1878 at Hadsel in Hadsel parish, Sofie was a bit older than her husband, as were many Norwegian brides. She was the youngest surviving child of her parents. Others included a half-brother Johan Martinessen, a sister Kaspara Helmine Sivertsdatter (Mina), and a brother Hans Sivertsen. As many as eight other siblings pre-deceased Sofie.

Sofie had a typical Norwegian upbringing. As a child, she walked a long way to school every day. Teenaged Sofie served as godmother to her brother Hans’ son Sydolf in 1894 and to her sister Mina’s daughter Helene in 1897. Before moving to Stokmarknes as a young woman, she lived for a time in a nearby village. There she cared for livestock for a man named Elias Knudsen, who was perhaps an uncle.

Most Norwegians during this time belonged to the state-supported Lutheran Church, and Ole and Sofie joined, too. She was confirmed June 18, 1893 at Eidsfjord parish, and he was confirmed on September 13, 1896 at Hadsel parish. The church recorded each confirmand’s knowledge of the catechism, as Very Good, Good, or Not So Good. Both Ole and Sofie had Good ratings.

After marrying Sofie, Ole left for America to make a home for his five-foot, four-inch, auburn-haired bride. He traveled first to the Norwegian port city Trondheim. On April 20, 1904, he started the next leg of his journey aboard the Cunard ship Salmo bound for Liverpool, England. There he boarded the Ivernia, and two weeks later on May 4, 1904 he arrived in Boston, Massachusetts. He took a train to Lake Park, Minnesota and worked there for the Northern Pacific Railroad earning a dollar a day. Sofie remained behind with her family to await the birth of her first child, Riborg Marie Hansene Bentsen (1904). Riborg’s baptism record states that her father lived in “Amerika”.

The following spring, Sofie and Riborg left Trondheim on the Tasso on April 12, 1905. They sailed on the Dominion from Liverpool and arrived in Quebec on May 3, 1905. Sofie remembered the trip well; the ship ran aground on a sandbar in the St. Lawrence and took several days to get moving again. When they finally could disembark, Sofie and her infant daughter traveled by train to Chicago and then on to Lake Park to meet Ole. They lived there for a couple of years and welcomed their first son, Bjarne Kaurin, into the family in 1906.

By 1907, they were ready to claim the free land the government offered on the grassy sea of eastern Montana. The family traveled together by train and landed in Culbertson, Montana on July 30, Sofie’s 29th birthday. Settling on a quarter section of land in a Scandinavian community near Medicine Lake, they built a two-room sod house that was lined with wood boards.

Another daughter, Signe Eline, joined them in 1908. The Bentsens had her baptized in a hayloft during a meeting of area ministers.

In 1909, in nearby Williston, North Dakota, Ole filed a Declaration of Intention to become a citizen of the United States. His application describes him as 5 feet 10 inches tall with black hair and brown eyes.

The new homesteaders tried to be self-sufficient. Sofie made the children’s clothes on a hand-powered sewing machine she had brought from Norway. She also knitted the family’s stockings. She even found time to do beautiful Hardanger embroidery. Still, Ole and Sofie found that making a living on just 160 acres in the arid west was not easy.

The U.S. government finally recognized the problem and began opening areas for larger homesteads of 320 acres. The Bentsens sold their quarter section and filed on a half section of land 13 miles southeast of Redstone, Montana, near the Canadian border.

In later years, they reminisced about that first summer of 1910 on the new place. They had few neighbors, and the family of five lived in a 10×12 foot shack that Ole built. But that summer the bright and beautiful Haley’s Comet appeared, relieving the tedium and loneliness.

The Bentsens had acquired livestock including three horses, some cows, sheep, and chickens. The new area had been surveyed only by township units at that time, so Ole estimated where his section line would be. He plowed a furrow to mark it, using his three horses and a walking plow. When the rest of the surveying was done, most of his fence posts stood in that furrow.

The first winter on the new homestead, Ole took a team and sled on a 35-mile trip back to Medicine Lake for supplies. While stopping over at his parents’ home near Homestead, he became ill with typhoid fever. He remained there for 6 weeks, leaving Sofie home alone with three little children, ages 6, 4, and two.

That winter was very hard for Sofie. Every morning she would go to the nearby creek to chop a hole in the ice so the livestock could water. One bleak day when all seemed hopeless with food and coal nearly gone, a couple of neighbors arrived. They brought her some coal and butchered a calf for her. The family all remembered the happy day when Ole finally returned home.

During the following summer of 1911, Ole built a two-room house which they added on to in later years. Originally, for illumination at night they used kerosene lamps, which they cleaned and filled daily. They dug a 15-foot well by hand. Ole hauled the first crop to the nearest railroad at Medicine Lake. Bjarne later recalled helping his father build a barn.

In the early years on the homestead, wild game was plentiful so Sofie cooked many meals of duck, prairie chicken, and rabbit. She did the cooking on a coal stove, and in summer the children gathered cow chips. They burned these in the stove, and it worked very well to save on coal. The family and their neighbors mined their own coal from a mine about five miles away.

Sofie did the clothes washing on a wash board, and she boiled sheets in a boiler. For wash water, she collected rain water in a barrel in summer and melted snow in the winter. If the rain barrel was empty, she would fill it with well water (which was very hard water), mix in some lye, and let it stand overnight. By morning the lye would settle and leave the water soft. She heated sad irons on the stove for ironing.

A bachelor homesteader arrived in the area and asked Sofie if she would bake bread for him. He said he had tried, but even his dog wouldn’t eat it. She baked for him as long as he was on the farm, into the 1920’s.

Coyotes were numerous and a menace. One morning Sofie was milking a cow when a coyote jumped out of the brush and killed a sheep just a few yards away. The coyote did not get to enjoy his kill because the Bentsens got the mutton.

The free range cattle in the area were very dangerous, too, and would attack anyone on foot. One day Ole’s horses broke loose and strayed, so Ole walked 30 miles to see if they had gone back to the Homestead area. On the way there, he was semi-surrounded by range cattle ready to attack. He waved his jacket at them. They retreated just far enough to allow him to duck below a nearby creek bank. He walked in a crouch along the creek until he was out of their sight. He later found the horses near Homestead and was able to ride back home.

Ole and some neighbors hauled lumber from Culbertson and built the Two Tree schoolhouse for the neighborhood. Riborg was one of the first students, and her parents began to learn to speak, read, and write in English when she started school. The community also used the school building as a community hall, church, site for pie and basket socials, and even an occasional dance. The school closed in the late 1940’s with Riborg’s daughter Shirley Bedwell serving as the last teacher.

One of the first years on the homestead, the family wanted a Christmas tree. Ole cut a poplar pole and drilled holes in it. He inserted juniper branches and they decorated it with little baskets and chains made of tissue paper. They also drained some eggs, wrapped the shells in tin foil, and hung them on the tree. Neighbors thought the tree was real and wondered where he got it.

The year 1918 was a busy one for the Bentsens. On July 8, 1918 Ole, Sofie, and their children became naturalized citizens of the United States at Plentywood, Montana. Bjarne, Signe, and Jennie Wilhelmine (born at home in 1916), were named in the naturalization process although they already were citizens, having been native-born. That summer Ole also registered for the WWI draft. He bought his first car, a 1918 Overland touring car which he did not use much that winter because the roads were poor and not plowed. The last child, Otto Sigurd, was born at home in November that year.

The next year, on July 26, 1919, Ole received a Patent for his 320 acres near Redstone in Sheridan County, Montana. He continued to farm the land for the next 33 years. In January 1952, he and Sofie sold their farm to their younger son, Otto, and his wife Bernice.

Ole and Sofie retired to Plentywood where Ole did Norwegian wood carving and made model boats. He also built a two-room storage area behind their small house. Sofie called it “Ole’s dog house.” Sofie was active in the ladies’ group at the Lutheran Church. She continued cooking and baking, making lefse and fattigmand every year for Christmas until 1965 when she fell ill.

Sofie died from emphysema and chronic bronchitis at age 87 on January 19, 1966 at Sheridan Memorial Hospital in Plentywood. She was buried on January 24 at Redstone Cemetery. At the time of her death, she had very little grey hair. She had always compared herself to one of her grandfathers who had lived to be 80 but also did not turn grey.

After Sofie died, Ole lived alone. He had given up his car and subsequently rode a bicycle around Plentywood until he was 90 years old. After that, he walked the 8 blocks to downtown. In the winter months he went to stay with his youngest daughter Jennie in Havre, Montana. This continued until 1972 when at age 92 he moved into Pioneer Manor in Plentywood.

After 10 years of widowhood, Ole died of uremia on his son Bjarne’s 70th birthday (August 26, 1976). Like Sofie, he passed away at Sheridan Memorial Hospital in Plentywood. He was 95 years old and still had a full head of white hair. He was buried beside Sofie on August 30 at Redstone Cemetery, Redstone, Montana.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 10—Laura Ruamy Riddle (1853-1933)

Laura Riddle’s name seems appropriate for a person who led a puzzling personal life with the men who fathered her children. After she reached adulthood, her family knew and referred to her as Laura Edmonds and a couple of her sons carried the Edmonds name, but she never used that name herself. Instead, she always conducted business and signed documents with her maiden name, Laura Riddle.

Laura Riddle’s name seems appropriate for a person who led a puzzling personal life with the men who fathered her children. After she reached adulthood, her family knew and referred to her as Laura Edmonds and a couple of her sons carried the Edmonds name, but she never used that name herself. Instead, she always conducted business and signed documents with her maiden name, Laura Riddle.

She began life ordinarily enough on October 9, 1853 as the fifth of eight children born to John Davis Riddle and Olive Dunbar. On their farm in Mendon Township, St. Joseph County, Michigan, she learned to keep house, raise crops, and care for livestock. She used these skills the rest of her life.

At about age 20, she reportedly married George Edmonds. Although women of her era usually married either in their home church or at their father’s house, no record of this marriage has been found in any county in Michigan. All her sisters and two brothers had marriages recorded in St. Joseph County, but Laura did not.

Laura and George did have three sons. Francis (Frank) was born in 1876 in adjacent Berrien County. Both Lewis and Joseph, in 1877 and 1880 respectively, were born in St. Joseph County. That year, George and Laura lived near Laura’s family while he worked as a laborer on a farm and she kept house.

After 1880, George Edmonds disappeared from Laura’s life. No divorce or death record for him has been found, but a man named George Edmonds did marry another woman in St. Joseph County in the early 1880’s. Laura seems to have been left alone to support three little boys, two of whom were always described as “slow”.

Like many other single women, she headed west to find opportunities for making a living. Her older sister Theodocia had already moved to Nebraska with her husband John Evert and their children. Laura joined them in McCook.

In January 1885, she settled north of McCook on a 160-acre tract adjacent to land owned by her brother-in-law in Red Willow County. On June 24, 1885, she went to the McCook Land Office and filed a pre-emption claim on the land. By then she had erected a 14×16 house with a door and 2 windows and had broken 18-20 acres. She reported herself to be a single woman, but oddly claimed to have just 2 children. Perhaps one son had actually stayed behind in Michigan for a while or was living with John and Theodocia Evert. Unfortunately, no record for Laura and her boys has been found on the 1885 Nebraska census, so we do not know who resided in her household that year.

That August the Land Office approved her claim. She paid the $200 cash entry fee, a rate of $1.25 per acre, for her land.

Laura remained in Red Willow County for several years. It must have been hard for her when John and Theodocia Evert decided in 1888 to relocate to the Sandhill region of northwestern Nebraska, near Hyannis. Laura stayed behind in the McCook area. Perhaps she had a boyfriend.

By 1892, Laura also decided to move on from the McCook area. She filed a claim on a 160-acre homestead north of Palisade, Nebraska in Hayes County, claiming she supported 3 children. There she and the boys built a 14×18 frame house and a sod stable, a cave cistern, a hog corral, and a chicken house. They cultivated 45 acres. In 1896, Laura’s daughter Grace was born there, father unknown. Laura received the final certificate for this homestead in January 1899.

Sometime during this period, her son Frank left the family home. He moved on to Wyoming and Montana, working as a sheepherder. He registered for the WWI draft in Big Horn County, Wyoming. In 1944 he died from a broken neck when he was thrown from a horse in Montana’s Lewis and Clark National Forest. He is buried in Great Falls, Montana.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Laura’s household in Hayes County consisted of herself (“Laura Riddle”) and three children (Lewis, Joseph, and Grace “Edman”). According to Grace’s sister-in-law, Bertha Reed Evert, “They were very hard up (or poor). Grandma [Theodocia] Evert went to visit Laura. Grandma Evert told me Laura was a widow then and was having a hard time making a living as the boys wasn’t (sic) big enough to get work all the time. So Grandma Evert brot (sic) Grace home with her.”

Bertha Evert thought Grace was about 2 years old when she went to live with the Everts, but the 1900 U.S. census for Hayes County lists 4-year-old Grace in her mother’s household. By 1910, however, 14-year-old Grace was enumerated with Theodocia Evert in Grant County. Interestingly, another member of the Evert household that year was a laborer named Samuel H. Reed, who later became Grace’s father-in-law.

Theodocia raised Grace as her own child and left Grace a share of her estate equal to that of her natural children when she died in 1929. How typical this was of the generous Theodocia whose son Warren’s wife, Blanche, described her as the “most kind and loving person I ever knew.”

Perhaps Grace’s move took place in 1904 when Laura and the boys decided to take new homesteads even further west in Dundy County, Nebraska. Congress had recently passed the Kincaid Act which allowed larger homesteads in western Nebraska. Several Palisade-area homesteaders sold their small farms and moved on. That year, Laura had inherited some money, $43.14, for her share of the proceeds from the sale of her mother’s farm in Michigan. Laura, Lewis, and Joseph sold their place in Hayes County for $350 and each filed claims on adjacent tracts near Haigler, Nebraska.

Again, poverty made life difficult. A neighbor’s affidavit described Laura as a poor widow who “has had to work where she could for a living while holding this [Dundy County] homestead. With her son they took nearby pieces of land without even a team to start with, buying a horse at a time”. She worked for a neighbor in Palisade in return for a wagon and harness. Eventually she improved the homestead to include a 20×26 house of stock boards with a board roof covered with tarred paper and sod, a well and pump, a corn crib, a stable and chicken house, 2 miles of wire fencing, 20 cottonwood trees, and 60 broken acres. She rented pasture space to neighbors.

Acquiring the final certificate for this homestead proved difficult. The case file is marked “Confidential” because neighbors contested her claim, alleging that she had not spent the requisite time actually living on the homestead. The Field Division in Cheyenne, Wyoming referred her case to the U.S. Land Office in Lincoln, Nebraska for investigation.

Her 480-acre Dundy County land finally proceeded to Patent in 1912. The investigator found “Inasmuch as the claimant was very poor when she took this land and has had to work for her living, and is well along in years, and seems to have complied with the law as to residence and as to improvements in a substantial manner, and apparently good faith, commensurate with her means and ability, I recommend that final certificate issue and the case pass to patent.” He suspected that at least one of the neighbors had given self-serving testimony in hopes of acquiring her land for himself.

Lewis and Joseph faced similar difficulties and allegations. Joseph’s land finally proceeded to patent, but Lewis surrendered his claim.

Lewis and Joseph continued to live with Laura and remained with her through most of their adult lives. About 1926, Laura and Joseph sold their homesteads and moved with Lewis back to Palisade, Nebraska. Joseph purchased a house in town, and the mother and sons lived there together. Their neighbor, Kenneth Ungles, recalled that Laura was a big, strong woman. He remembered Lewis and Joseph doing odd jobs like raking leaves.

Laura passed away from a stroke on September 2, 1933. She left an estate of personal property worth $900; Joseph received all of it as compensation for taking care of his mother from 1929-1933. Lewis died a couple of years later on November 23, 1935. When Joseph became too infirm to care for himself in 1949, Clyde Coles, the same man who had rented pasture land from Laura 40 years earlier, became his guardian. Joseph died on January 3, 1956. The mother and her two sons are buried next to each other with a single headstone in the Palisade Cemetery.

Regardless of the mysteries surrounding the men in her life, some things about Laura Riddle are very clear. She led a hard life. She struggled as a single mother to support disabled children, and she had to give one child away. She endured spitefulness and condescension from some of her neighbors. Yet she also made life-long friends and had the support of a loving sister. Despite every hardship, she always made her own way and never gave up.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 9—A Mystery Man

Great-grandfather, who are you?

Great-grandfather, who are you?

The identity of one of my great grandfathers remains a mystery to me. My grandmother Grace Riddle Reed stated that she did not know her father’s name and never met him.

Grace was born on a homestead near Palisade, Nebraska on August 30, 1896. Her mother was Laura Riddle, and Grace had three much-older brothers (probably half-siblings), Francis, Lewis, and Joseph.

Laura was supposed to have been married in Michigan in the 1870’s to George Edmonds although no marriage record for them has been found. George seemed to be out of the picture by the time Laura relocated to Nebraska with her sons in the mid-1880’s. By then, Laura had resumed using her maiden name Riddle, and her middle son Lewis went by that surname, too. Francis and Joseph continued to go by the Edmonds name. As far as I know, Laura never remarried.

Grace was born while Laura worked her second homestead near Palisade, Hayes County, Nebraska more than ten years after moving to that state. We have no clues in our family papers for the identity of Grace’s father. We know only of these associates of Laura:

- George Edmonds. Perhaps Laura reconnected with him at some point, either if he traveled through Nebraska or she returned home to Michigan for a visit.

- Robert Mickey and Wm. Hyatt. These men witnessed Laura’s intent to make proof of her claim for her first homestead near McCook, Red Willow County, Nebraska in June, 1885.

- William F. Smith and John Lane (Layne). These men also witnessed her intent to make proof, and they subsequently executed affidavits in support of her homestead claim in August, 1885.

- Cyrus “Si” Smith. Laura worked at his wagon and harness shop in Palisade, Nebraska. He executed an affidavit in support of her Palisade homestead in 1898.

- Richard Ryan. He also executed an affidavit on her behalf in 1898.

- Leslie Lawton. By 1904, Laura knew this Civil War veteran, and she also worked for him near Palisade. He was instrumental in encouraging her to relocate from Palisade to Haigler, Dundy County, Nebraska to take up a larger homestead. They lived together for a time while Lawton was separated from his wife.

- Clyde Cole. This son-in-law of Leslie Lawton homesteaded on a place adjacent to Laura’s in Dundy County. In later years, he served as guardian to her son Joseph Edmonds.

- Wm. Palmer and C. F. Fay. These men served as witnesses for Laura’s intent to make proof of her Dundy County homestead in 1911.

- B. H. Bush, and W. J. Hacker. These men signed affidavits in support of Laura’s Dundy County homestead application in 1912.

Would any of these men be a likely candidate for my great-grandfather? Someone fathered Laura’s little girl at the end of 1895, but she did not disclose that information to her daughter.

I think the only way we will ever learn his identity is through a DNA match. My father has taken a couple of autosomal DNA tests, and he inherited 25% of his DNA from our mystery man. Perhaps we can uncover a match if another descendant of my great-grandfather ever takes such a test.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 8—Anna Petronellia Sherman (1865-1961)

Anna Petronellia Sherman lived a very long life. According to death certificate information provided by her son Thomas Aaron Reed, she was born on April 1, 1865 to Thomas Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh and died in Clinton, Missouri in 1961 at the age of 95. Contrary to the information on her death certificate, she was probably born in Indiana. No record of her mother has been found, and family lore claims that she died in Indiana before 1870. The mother was reportedly from Germany or Holland, making little Petronellia either half German or half Dutch.

Anna Petronellia Sherman lived a very long life. According to death certificate information provided by her son Thomas Aaron Reed, she was born on April 1, 1865 to Thomas Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh and died in Clinton, Missouri in 1961 at the age of 95. Contrary to the information on her death certificate, she was probably born in Indiana. No record of her mother has been found, and family lore claims that she died in Indiana before 1870. The mother was reportedly from Germany or Holland, making little Petronellia either half German or half Dutch.

The motherless girl strongly disapproved when her father remarried 19-year-old Alice Farris in 1881. Ironic then, that two years later on September 6, 1883 Petronellia herself, at the age of 18, married an older widower, 38-year-old Samuel Harvey Reed, in Coles County, Illinois. She became the stepmother to his two daughters, Annie and Clara. He called her “Pet” and drove her around in a buggy while she held a fancy parasol. She later said she was attracted to his big, white house (which actually belonged to his father) and to the highly-respected Reed name. The Reeds, in turn, hardly approved of Samuel marrying the daughter of a poor blacksmith who drank, especially when Samuel’s first wife had been very well off. Samuel immediately moved his new bride to Kansas and later, to Missouri. They had seven children: Bertha Evaline (1884), Caleb Logan (1887), Viola May (1889), Robert Morton (1891), Samuel Carter (1892), Thomas Aaron (1894), and Owen Herbert (1896 or 1897).

People who knew Petronellia have described her as temperamental, religious, and hard-working. Sometimes she kept a perfect house; at others she allowed chickens indoors. One time she chopped down all the trees in her yard because the songbirds annoyed her early in the morning. She had a fiery temper and could not get along with others. She and Samuel divorced in 1904.

She joined the No. 1 Methodist Church in Mountain Grove, Missouri when she was 23 and remained a member for the next 73 years. She read the Bible completely more than 20 times, played the church organ, and taught Sunday School until she was in her 90’s. She lived a simple, frugal life without an indoor toilet. If her children tried to give her money, she would donate it to Boy’s Town in Nebraska.

Petronellia worked for the Post Office off and on. She met Samuel Reed while working at the Charleston, Illinois post office. She was the first Postmaster at Graff, Missouri, serving from 1895 to 1899.

After her divorce from Samuel Reed, she married Captain James W. Coffey, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War, in 1906 in Texas County, Missouri. Some of her sons worked on Coffey’s farm. The marriage lasted only a few years and ended in divorce. With her children grown and no husband, Petronellia needed to earn a living.

She resumed the Reed surname and decided to apply for a homestead. Selling a proved-up homestead was a good way for single women to build a nest egg. To do so, she needed to move to a public-land state with homesteads available.

Several of her younger children had relocated to the Nebraska-Wyoming area, and her son Robert Morton Reed was the railroad station agent at Farthing, Wyoming, near Iron Mountain in Laramie County northwest of Cheyenne. Petronellia joined him there and took up a stock-raising homestead in 1918. She raised chickens and a few head of cattle, and she tried to grow some crops, without much success. One year, she harvested only a bucketful of potatoes. She became a crack-shot antelope hunter to survive.

By the end of her five-year homestead term, her son’s family had moved on to Wheatland, Wyoming with his railroad job. Petronellia hated the cold, windy, treeless prairie, so she sold her homestead and moved alone back to Missouri. Her homestead is now part of the large Farthing Ranch.

She lived out the rest of her long life in Mountain Grove, Missouri, growing blind in old age and eventually moving into a nursing home the last year of her life. She is buried in the churchyard of the No. 1 Methodist Church. She lies next to the grave of her daughter Bertha’s unnamed stillborn daughter who had been laid to rest there over 50 years earlier, in 1909.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks No 7: Samuel Harvey Reed (1845-1928)

Some people live in one place all their lives. A few even stay in the same house. They spend a lifetime in familiar surroundings with their families and longtime friends and neighbors. Samuel Harvey Reed was not one of those people. He had “that Reed wanderlust” and always felt drawn to a new opportunity in another Western state.

Early Life

Sam was born on April 9, 1845 in Ashmore Township, Coles County, Illinois, the firstborn of Joseph Caleb Reed and Janete (aka Jane) Carter. Both the Reed and the Carter families had traveled from Kentucky to become pioneer settlers in the Ashmore area around 1830. When Sam was born fifteen years later, the area remained very rural. As he grew up, ten-year-old Sam would have seen the 1855 construction of the Coles County Poor Farm in the township. The village of Ashmore would not be incorporated until after the Civil War in 1867.

Young Sam worked as a laborer on his father’s farm. Both his mother and father came from large families, so in addition to his own ten siblings, he had many cousins nearby. His mother had joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church a few years before he was born, and that is where he likely attended services. He learned to read and write at the local grammar school.

Whether or not Sam served in the Civil War remains the unresolved question of his young adulthood. He was certainly the right age for enlistment, turning 18 in 1863. Some of his relatives saw military service. His cousin Nancy Reed Ashmore’s husband, Hezekiah Ashmore, served the Union as a lieutenant in the 123rd Illinois Infantry. Two of his Boyd cousins served in the 8th Illinois, and both died in the War. Robert died from wounds received at Ft. Donelson, and George died at Vicksburg.

Did Sam enlist, too? Unlike Hezekiah Ashmore and the Boyd brothers, most men who served from Coles County came from the western side of the county. Settlers on the eastern side, like the Reeds, had migrated from Kentucky. They harbored southern sympathies and hated abolitionists even though they personally had not owned slaves. They opposed the draft and avoided the Army.

No record of military service for Sam has been found. The National Archives has no service file, nor did Sam ever file for a pension based on military service. No record of his membership in the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans, has been found. His name does not appear on the list of service men from Coles County or on the roster of any Illinois unit. Interestingly, neither does the name of his cousin Caleb Robertson Reed who was also said to have served. Searches have not been done for his remaining Reed and Carter cousins.

Could Sam have served from another state? Perhaps, although he resided on his father’s Illinois farm both before and after the war. It is possible, though, that he went away to enlist and then returned when he completed his service.

Despite the lack of proof, Sam and his family always claimed that he did fight for the Union. His daughter Bertha remembered that he would carry the flag while marching in parades with the Grand Army of the Republic. The family also offered service information whenever the question appeared on a census enumeration. The 1885 census for Edwards County, Kansas states that he enlisted in Illinois and served on pontoons. The 1890 Special Schedule of Surviving Soldiers for Texas Co., MO, reports that he served from April 9 – November 4, 1864 as a Private in Co. H, 8th Kansas Infantry, yet his name does not appear on this unit roster. The 1910 U.S. census for Grant County, Nebraska indicates simply that he served in the Union Army.

Family lore offers an unconvincing explanation for the lack of service documentation. They say that while returning home from the Civil War, Sam’s boat capsized. He was saved, but he lost all of his papers. The boat accident may be a true story, but why would Samuel have been carrying the only existing proof of his enlistment? There would have been official records kept elsewhere.

So did he serve? We have only his word that he did.

Marriage to Nancy Jane Dudley

A few years after the war, Sam married his neighbor Nancy Jane Dudley, daughter of Guilford Dudley and Mary Wiley, on August 1, 1869 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. Sam’s younger sister Emma Jane also married into the Dudley family a few years later.

This close connection to the prominent Dudleys thrilled the Reeds. The Dudleys descended from Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favorite of Queen Elizabeth I of England. The family also counted Sir Thomas Dudley, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, among their ancestors. A group of three Dudley brothers, including Nancy’s father, had been the first white people to settle in the Ashmore area of Illinois. They founded a now-defunct town called Bachelorsville where Guilford Dudley ran a store. Indians often traded at his store.

After their marriage, Sam and Nancy moved west to Centerville Township, Neosho County, Kansas. The Osage Indians had recently ceded the area, and settlers flocked in. The family of author Laura Ingalls Wilder settled a few miles away at the same time. Unfortunately, Charles Ingalls chose land that had not been ceded, and the government evicted him as a squatter some months later. Sam did not make that mistake.

For unknown reasons, the Reeds did not stay long in Kansas, either. They farmed that summer of 1870, and their first child, Anna Reed, was born there on August 23. Later in the year, they made arrangements to sell out and return to Illinois. Perhaps Nancy could not cope with homesteading life after Anna’s birth and needed to return to her family. When she died 10 years later, her death record stated that she had suffered from anemia for a decade.

By 1872, the Reeds had settled again in Illinois. Sam witnessed the will of his cousin Mary E. Reed on April 12, 1872 at Ashmore. Nancy delivered a second daughter, Amy, on July 13 the same year. A third daughter, Clara, was born at Bachelorsville on July 8, 1875.

Three months later, on September 21, 1875, little Amy Reed passed away at the age of 3. Her death was not recorded in the county record, so her cause of death remains unknown. That year Nancy and the other heirs of Guilford Dudley had donated land southwest of Ashmore to create a cemetery adjacent to the Enon Baptist Church. Amy was buried on these grounds.

Sam and Nancy continued to live in the Ashmore area although not always in Coles County. In 1879 they resided in Douglas County, just north of Coles. By the next year, they had returned to Ashmore, and Nancy was pregnant again. On July 2, the census taker visited their house and listed the Reed household members as Sam, Nancy, Anna, and Clara.

The next day, July 3, 1880, a fourth daughter, Mary Jane, was born. Nancy died in childbirth. Sources conflict on whether Mary Jane died the same day or lived for up to a month. Mother and daughter were buried alongside Amy Reed in the Enon Cemetery.

Marriage to Anna Petronellia Sherman

Suddenly, Sam Reed found himself a widower with two daughters, ages 10 and 5. He must have turned to his family for some help over the following months, but he needed a wife. He noticed a young woman working in the Post Office. She was Anna Petronellia Sherman, daughter of Thomas Lane Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh/Stillenbaugh [Stillabower/Stilgenbauer?].

They married on September 6, 1883 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. She was 18, he was 38, and his family was dismayed to see him wed the daughter of a poor, alcoholic blacksmith. But Sam delighted in his pert, young wife. As she carried a parasol against the sun, he drove her around in a carriage and called her “Pet”.

Then once again, Sam took his bride to Kansas. On August 31, 1884, his fifth daughter, Bertha Eveline, was born in Harper County. By mid-1885 the family, consisting of Sam, Petronellia, Clara, and Bertha, had moved on to Franklin Twp., Edwards County, Kansas. Presumably, 14-year-old Anna remained in Illinois with her grandparents.

Yet again, Sam did not stay long in Kansas. He soon relocated to Missouri where he raised hogs and a few cattle. There, on October 20, 1887, his first son and sixth child, Caleb Logan, was born in Upton Township, Texas County, Missouri. As was family tradition, the boy was known by his middle name “Logan”, and he was followed by Viola Mae on April 20, 1889, Robert Morton “Mort” on March 14, 1891, Samuel Carter “Cart” on October 2, 1892, Thomas Aaron “Aaron” on September 17, 1894, and Owen Herbert “Herb” on December 6, 1896.

Sam and his family have not been found on the 1900 U.S. census although they continued to live in Missouri through the 1890’s. Clara had gone to nursing school there and then married Gwinn Routledge at Rolla in 1898. Petronellia was postmaster at Graff from 1895-1899. But the Reed marriage was in decline, and we have no record proving that Sam remained with his family during these years. After all, he was increasingly a wanderer.

On May 26, 1904 he and Petronellia divorced at Houston, Texas County, Missouri. Petronellia asked for custody of all her children including Bertha, who had married Charles Richards in Oklahoma earlier that year. The court required Sam to pay his wife alimony in the sum of eighty dollars cash and to convey his 200-acre farm in Texas County to her. He also had to pay her legal fees and cancel her $150 debt to him. In return, Petronellia released her dower right to Sam’s Wright County farm.

Samuel, the Wanderer

After that, Sam seems to have taken off on a 20-year itinerant life. Even his appearance changed. He had previously worn a full beard, but now he shaved off most of his whiskers to leave only a mustache.

By 1910 he worked on a western Nebraska ranch owned by a kindly woman named Theodocia Evert. She was a widow whose own family was grown but who was raising her sister’s teenage daughter, Grace Riddle. That summer, Sam’s son-in-law Charles Richards joined him on the ranch work crew. In a horrifying haying accident, Charles lost his legs. Bertha and their two children traveled from Missouri to Nebraska to nurse him back to health. The Richards marriage, already troubled, did not survive this tragedy, and they subsequently divorced. Bertha later married Theodocia Evert’s son Henry and remained in Nebraska for the rest of her life.

It is unclear how long Sam remained in Nebraska, but several of his children settled there in the years before World War I. Cart and Aaron homesteaded in Cherry County. Herbert took a turn working on the Evert ranch and married Grace Riddle. Viola lived nearby for a while and married Bert Gwinn at Alliance in 1919. She, Cart, and Aaron all served in World War I from Nebraska.

After his stint in Nebraska, Sam spent some time in Oklahoma. Oil had been discovered there, and Sam looked to invest. When his parents died in 1903 and 1907, he did not want the Illinois farm and inherited money instead. Mort’s children remembered that despite Sam’s high hopes, the oil play did not go well. Complicating the situation, Sam had become involved with a woman and then suspected her of wanting only his land and money. It is unclear whether or not he had married her. Mort finally travelled to Oklahoma to help resolve matters for his father. After this incident, Sam’s whereabouts are unknown, and he has not been positively identified on the 1920 U.S. census.

Later, after living in the western states for nearly 40 years, Sam returned to his home town when he was in his mid-seventies. In 1922 he began living with his eldest daughter Anna McDavitt and her family about 2 miles east of Ashmore, Illinois. Sometimes he experienced anxiety attacks and the urge to “go somewhere”. Other than that, he was in generally fair health although he had circulation problems and an enlarged prostate.

By 1927 he displayed more symptoms of age-related mental decline. He became increasingly wild and destructive around the house and did not keep himself clean. He suffered from hallucinations and chattered nervously about imaginary events. After an especially severe attack that required sedation, Anna realized she could no longer keep him at home. She had him declared incompetent, and committed him to the Jacksonville State Hospital for the Insane. There he died in his sleep a month later on October 2, 1928 at the age of eighty-three.

His body was returned to Ashmore for burial. His grandson Joseph VanMeter McDavitt (“Van”) earned $5 for cleaning up and readying the burial plot. After a funeral at the Baptist church with a Presbyterian minister officiating, Samuel was laid to rest in the Enon Cemetery next to his first wife Nancy and their daughters Amy and Mary Jane.

Sam’s estate consisted only of some money in the Ashmore bank. He had not led an industrious life, and most of his inheritance had been lost in poor land deals. After payment of his final expenses, $549.81 remained. Distribution to his nine surviving children amounted to $61.09 each, but Viola and Mort refused to accept their shares. They directed that their inheritance should go to Anna to compensate her for caring for their father.

Although Samuel did not leave large sums to his children, he did give them some valuable advice. They all remembered that he often said, “You inherited a good name, now keep it that way.” He may have wandered about and squandered his money, but he always kept what he valued most, his good name.

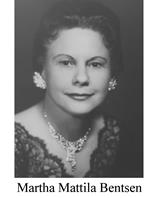

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 6—Martha Louise Mattila (1906-1977)

My maternal grandmother Martha had a multicultural upbringing. Her parents Alexander and Ada had immigrated from Viipuri, Finland in 1905, the year before she was born. They settled on the Iron Range of Minnesota, near Hibbing. Martha was their first child, and they spoke Finnish at home.

My maternal grandmother Martha had a multicultural upbringing. Her parents Alexander and Ada had immigrated from Viipuri, Finland in 1905, the year before she was born. They settled on the Iron Range of Minnesota, near Hibbing. Martha was their first child, and they spoke Finnish at home.

At that time, Hibbing was still getting settled after its founding in 1892. The mining companies heavily recruited in eastern and southern Europe to find workers. Martha grew up among various ethnic groups including Poles, Bohemians, and Italians. She also had an extended Finnish family nearby, because three of her father’s sisters immigrated, too. She met her life-long friend Melia when she started school.

Martha’s own family attended the Lutheran Church, but many of the neighbors were Roman Catholic. She spoke of the time when she was about five years old, and she heard a Catholic bishop was coming to town. There must have been some anxious preparation in the community for this occasion because Martha was so afraid that she hid under the bed. “And I wasn’t even Catholic,” she laughed later.

Martha spent her early years believing she would be an only child. Not until she was 10 did another sister, Aida, arrive in 1916. Two brothers followed: Hugo in 1918, and Peter in 1919. Martha suddenly found herself in the role of mother’s helper.

She was a smart girl, and despite her household duties, she finished high school early. She went on to college at the Duluth branch of the University of Minnesota. There she earned a two-year certificate in elementary education. Martha became a teacher.

She sought adventure and applied for a job far away in Montana. With her ability to mingle easily among other ethnic groups, she was hired to teach in a Norwegian community near Redstone, Montana. She taught at a one-room schoolhouse and lived with local farm families.

On 2 June 1928 she married Bjarne Bentsen, the older brother of two of her students, Jennie and Otto. For a year or so, until the birth of their daughter Joyce, Martha and Bjarne stayed in Montana. Sometime in 1929 they decided to relocate to Martha’s hometown, Hibbing.

They settled into a house that her father had built, right next door to her parents and younger siblings. Martha focused on raising Joyce and eventually had two more children, a son Ronald (“Sonny”) and another daughter. She had a somewhat fractious relationship with her mother but also enjoyed gossiping with her in their native Finnish language. Her children felt as much at home in their grandparents’ house as they did in their own.

The family remained in Hibbing, except for a short-lived move to a larger house, until Martha’s parents had both died. Then Bjarne got the itch to return to the West. He hoped to become an electrician to capitalize on the post-War building boom.

They uprooted their family and drove to Wyoming. Bjarne worked as an electrician here and there for the next few years while Martha supplemented the family income by teaching school. They finally landed in Rapid City, South Dakota, where he set up an electrical shop. Their youngest child graduated from high school and got married. But these happy events could not outweigh the stress of constant moves and uncertain income. Their marriage fell apart.

Bjarne and Martha divorced in 1960, and Martha remained in their little house. At first she enjoyed life by socializing with the neighbors and participating in veteran’s groups. She served as President of local chapters of both the VFW Auxiliary and the American Legion Auxiliary. Martha loved to dance and faithfully attended the weekly dances at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City. She really liked dancing with all the young airmen.

Bjarne and Martha divorced in 1960, and Martha remained in their little house. At first she enjoyed life by socializing with the neighbors and participating in veteran’s groups. She served as President of local chapters of both the VFW Auxiliary and the American Legion Auxiliary. Martha loved to dance and faithfully attended the weekly dances at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City. She really liked dancing with all the young airmen.

Yet her carefree life as a divorcee did not last long. Bjarne was not good at paying his alimony, so Martha continually scrambled for money. For a few semesters, she offered room and board to students from the South Dakota School of Mines. She continued to teach school off and on, first at the Bergquist School in Rapid City. After the school district began requiring teachers to have a 4-year degree, she began commuting to teach at the rural Fairburn school where her 2-year diploma still sufficed.

When it came time to collect Social Security, she found she did not have enough work credits to qualify. Martha found a job in a local bakery where she worked until she could receive benefits.

Eventually the time came when she needed to sell her house. The upkeep had become strenuous, and she wanted to unlock the equity in the home. She hated leaving the neighborhood she had known for over twenty years, but she made friends quickly in her new apartment complex.

She lived there until 1977 when her health began to fail. Her daughter Joyce took Martha into her home in Casper, Wyoming. After a short time, it became apparent that Martha needed a nursing home. She hated it there and lasted only three months. On the 26th of August 1977 (Bjarne’s birthday) she passed away after a stroke.

Martha was not particularly religious, and she did not have a church funeral. The family held a simple memorial service for her in a funeral home chapel. She was buried in the Highland Cemetery in Casper.

Martha liked pretty things, and she did beautiful crochet work. Her family still has her china, silver service, and many afghans and doilies that she made.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks no. 5–Bjarne Kaurin Bentsen (1906-1986)

My grandfather Bjarne occupied the slot of the first child in his family born in America. He took that role very seriously, and when he grew up he promptly anglicized his name to Barney.

My grandfather Bjarne occupied the slot of the first child in his family born in America. He took that role very seriously, and when he grew up he promptly anglicized his name to Barney.

His parents, grandparents, and older sister Riborg had emigrated from Bø in the far northern reaches of Norway in 1904 and 1905. Upon their arrival in the United States, they settled temporarily in Lake Park, Minnesota. Bjarne’s father and grandfather went to work for the railroad to earn enough money to homestead in the West. While the family lived in Lake Park, Bjarne was born on 26 August 1906.

By 1907 the family had saved enough to begin homesteading. Bjarne travelled on the train with his family to Culbertson, Montana. From there they headed north to the Medicine Lake area and acquired homesteads among other Norwegian settlers. A few years later, Bjarne’s parents moved on to a larger homestead in Sheridan County near Redstone, Montana, just south of the Canadian border.

On the new homestead, Bjarne helped his dad build a sturdy barn that still stands on the property over a hundred years later. They spoke Norwegian at home, and Bjarne did not begin to learn English until his sister Riborg started school. During his youth, he learned to hunt and fish, a pastime that became a life-long pursuit.

Bjarne and his siblings Riborg, Signe, Jennie, and Otto attended the Two Tree School about a mile from their home. Their father had built the structure.

Long after Bjarne had finished the eighth grade at Two Tree, a pert, new teacher arrived from Minnesota to take over instruction at the school. Martha Mattila lived with surrounding farmers, including the Bentsens, during the school year. Bjarne took a shine to her, and they were married on 2 June 1928 in Plentywood, the county seat. For unknown reasons, they wed at the Congregational Church even though both were Lutheran.

They welcomed their first child, my mother Joyce, the next year. The local paper reported that “Mother and daughter are getting along nicely and Mr. Bentsen is wearing the smile that won’t come off.”

Once he started his family, Bjarne no longer wanted to help with the farming; he seemed ready to try something new. He and Martha left Montana to return to her old neighborhood in Hibbing, Minnesota. By 1930 they had moved into a house next door to her parents, and Bjarne went to work as an electrician for the local iron mine.

During the Depression, Bjarne and Martha added a son and another daughter to their family. Bjarne changed lines of work again, leaving the mines to become a police officer.

His family recalled encountering him in his official capacity during those years. He occasionally had to pick up his disorderly brothers-in-law at the taverns. Sometimes he stopped in at home in the evenings to tell his children it was time for lights out. His worst experience was identifying the body of his father-in-law after Alex Mattila was killed by a train in 1945.