52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks No 7: Samuel Harvey Reed (1845-1928)

Some people live in one place all their lives. A few even stay in the same house. They spend a lifetime in familiar surroundings with their families and longtime friends and neighbors. Samuel Harvey Reed was not one of those people. He had “that Reed wanderlust” and always felt drawn to a new opportunity in another Western state.

Early Life

Sam was born on April 9, 1845 in Ashmore Township, Coles County, Illinois, the firstborn of Joseph Caleb Reed and Janete (aka Jane) Carter. Both the Reed and the Carter families had traveled from Kentucky to become pioneer settlers in the Ashmore area around 1830. When Sam was born fifteen years later, the area remained very rural. As he grew up, ten-year-old Sam would have seen the 1855 construction of the Coles County Poor Farm in the township. The village of Ashmore would not be incorporated until after the Civil War in 1867.

Young Sam worked as a laborer on his father’s farm. Both his mother and father came from large families, so in addition to his own ten siblings, he had many cousins nearby. His mother had joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church a few years before he was born, and that is where he likely attended services. He learned to read and write at the local grammar school.

Whether or not Sam served in the Civil War remains the unresolved question of his young adulthood. He was certainly the right age for enlistment, turning 18 in 1863. Some of his relatives saw military service. His cousin Nancy Reed Ashmore’s husband, Hezekiah Ashmore, served the Union as a lieutenant in the 123rd Illinois Infantry. Two of his Boyd cousins served in the 8th Illinois, and both died in the War. Robert died from wounds received at Ft. Donelson, and George died at Vicksburg.

Did Sam enlist, too? Unlike Hezekiah Ashmore and the Boyd brothers, most men who served from Coles County came from the western side of the county. Settlers on the eastern side, like the Reeds, had migrated from Kentucky. They harbored southern sympathies and hated abolitionists even though they personally had not owned slaves. They opposed the draft and avoided the Army.

No record of military service for Sam has been found. The National Archives has no service file, nor did Sam ever file for a pension based on military service. No record of his membership in the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans, has been found. His name does not appear on the list of service men from Coles County or on the roster of any Illinois unit. Interestingly, neither does the name of his cousin Caleb Robertson Reed who was also said to have served. Searches have not been done for his remaining Reed and Carter cousins.

Could Sam have served from another state? Perhaps, although he resided on his father’s Illinois farm both before and after the war. It is possible, though, that he went away to enlist and then returned when he completed his service.

Despite the lack of proof, Sam and his family always claimed that he did fight for the Union. His daughter Bertha remembered that he would carry the flag while marching in parades with the Grand Army of the Republic. The family also offered service information whenever the question appeared on a census enumeration. The 1885 census for Edwards County, Kansas states that he enlisted in Illinois and served on pontoons. The 1890 Special Schedule of Surviving Soldiers for Texas Co., MO, reports that he served from April 9 – November 4, 1864 as a Private in Co. H, 8th Kansas Infantry, yet his name does not appear on this unit roster. The 1910 U.S. census for Grant County, Nebraska indicates simply that he served in the Union Army.

Family lore offers an unconvincing explanation for the lack of service documentation. They say that while returning home from the Civil War, Sam’s boat capsized. He was saved, but he lost all of his papers. The boat accident may be a true story, but why would Samuel have been carrying the only existing proof of his enlistment? There would have been official records kept elsewhere.

So did he serve? We have only his word that he did.

Marriage to Nancy Jane Dudley

A few years after the war, Sam married his neighbor Nancy Jane Dudley, daughter of Guilford Dudley and Mary Wiley, on August 1, 1869 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. Sam’s younger sister Emma Jane also married into the Dudley family a few years later.

This close connection to the prominent Dudleys thrilled the Reeds. The Dudleys descended from Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favorite of Queen Elizabeth I of England. The family also counted Sir Thomas Dudley, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, among their ancestors. A group of three Dudley brothers, including Nancy’s father, had been the first white people to settle in the Ashmore area of Illinois. They founded a now-defunct town called Bachelorsville where Guilford Dudley ran a store. Indians often traded at his store.

After their marriage, Sam and Nancy moved west to Centerville Township, Neosho County, Kansas. The Osage Indians had recently ceded the area, and settlers flocked in. The family of author Laura Ingalls Wilder settled a few miles away at the same time. Unfortunately, Charles Ingalls chose land that had not been ceded, and the government evicted him as a squatter some months later. Sam did not make that mistake.

For unknown reasons, the Reeds did not stay long in Kansas, either. They farmed that summer of 1870, and their first child, Anna Reed, was born there on August 23. Later in the year, they made arrangements to sell out and return to Illinois. Perhaps Nancy could not cope with homesteading life after Anna’s birth and needed to return to her family. When she died 10 years later, her death record stated that she had suffered from anemia for a decade.

By 1872, the Reeds had settled again in Illinois. Sam witnessed the will of his cousin Mary E. Reed on April 12, 1872 at Ashmore. Nancy delivered a second daughter, Amy, on July 13 the same year. A third daughter, Clara, was born at Bachelorsville on July 8, 1875.

Three months later, on September 21, 1875, little Amy Reed passed away at the age of 3. Her death was not recorded in the county record, so her cause of death remains unknown. That year Nancy and the other heirs of Guilford Dudley had donated land southwest of Ashmore to create a cemetery adjacent to the Enon Baptist Church. Amy was buried on these grounds.

Sam and Nancy continued to live in the Ashmore area although not always in Coles County. In 1879 they resided in Douglas County, just north of Coles. By the next year, they had returned to Ashmore, and Nancy was pregnant again. On July 2, the census taker visited their house and listed the Reed household members as Sam, Nancy, Anna, and Clara.

The next day, July 3, 1880, a fourth daughter, Mary Jane, was born. Nancy died in childbirth. Sources conflict on whether Mary Jane died the same day or lived for up to a month. Mother and daughter were buried alongside Amy Reed in the Enon Cemetery.

Marriage to Anna Petronellia Sherman

Suddenly, Sam Reed found himself a widower with two daughters, ages 10 and 5. He must have turned to his family for some help over the following months, but he needed a wife. He noticed a young woman working in the Post Office. She was Anna Petronellia Sherman, daughter of Thomas Lane Sherman and Catherine Stanabaugh/Stillenbaugh [Stillabower/Stilgenbauer?].

They married on September 6, 1883 at Ashmore, Coles County, Illinois. She was 18, he was 38, and his family was dismayed to see him wed the daughter of a poor, alcoholic blacksmith. But Sam delighted in his pert, young wife. As she carried a parasol against the sun, he drove her around in a carriage and called her “Pet”.

Then once again, Sam took his bride to Kansas. On August 31, 1884, his fifth daughter, Bertha Eveline, was born in Harper County. By mid-1885 the family, consisting of Sam, Petronellia, Clara, and Bertha, had moved on to Franklin Twp., Edwards County, Kansas. Presumably, 14-year-old Anna remained in Illinois with her grandparents.

Yet again, Sam did not stay long in Kansas. He soon relocated to Missouri where he raised hogs and a few cattle. There, on October 20, 1887, his first son and sixth child, Caleb Logan, was born in Upton Township, Texas County, Missouri. As was family tradition, the boy was known by his middle name “Logan”, and he was followed by Viola Mae on April 20, 1889, Robert Morton “Mort” on March 14, 1891, Samuel Carter “Cart” on October 2, 1892, Thomas Aaron “Aaron” on September 17, 1894, and Owen Herbert “Herb” on December 6, 1896.

Sam and his family have not been found on the 1900 U.S. census although they continued to live in Missouri through the 1890’s. Clara had gone to nursing school there and then married Gwinn Routledge at Rolla in 1898. Petronellia was postmaster at Graff from 1895-1899. But the Reed marriage was in decline, and we have no record proving that Sam remained with his family during these years. After all, he was increasingly a wanderer.

On May 26, 1904 he and Petronellia divorced at Houston, Texas County, Missouri. Petronellia asked for custody of all her children including Bertha, who had married Charles Richards in Oklahoma earlier that year. The court required Sam to pay his wife alimony in the sum of eighty dollars cash and to convey his 200-acre farm in Texas County to her. He also had to pay her legal fees and cancel her $150 debt to him. In return, Petronellia released her dower right to Sam’s Wright County farm.

Samuel, the Wanderer

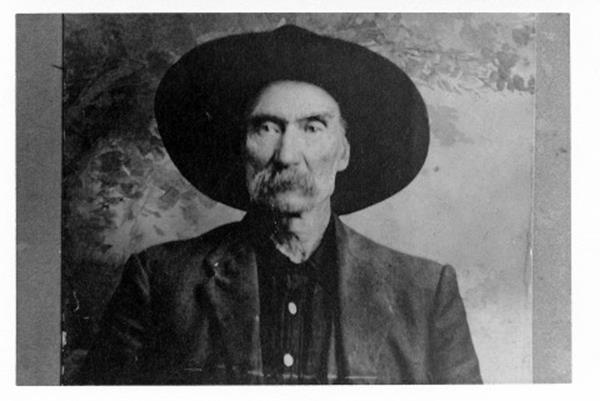

After that, Sam seems to have taken off on a 20-year itinerant life. Even his appearance changed. He had previously worn a full beard, but now he shaved off most of his whiskers to leave only a mustache.

By 1910 he worked on a western Nebraska ranch owned by a kindly woman named Theodocia Evert. She was a widow whose own family was grown but who was raising her sister’s teenage daughter, Grace Riddle. That summer, Sam’s son-in-law Charles Richards joined him on the ranch work crew. In a horrifying haying accident, Charles lost his legs. Bertha and their two children traveled from Missouri to Nebraska to nurse him back to health. The Richards marriage, already troubled, did not survive this tragedy, and they subsequently divorced. Bertha later married Theodocia Evert’s son Henry and remained in Nebraska for the rest of her life.

It is unclear how long Sam remained in Nebraska, but several of his children settled there in the years before World War I. Cart and Aaron homesteaded in Cherry County. Herbert took a turn working on the Evert ranch and married Grace Riddle. Viola lived nearby for a while and married Bert Gwinn at Alliance in 1919. She, Cart, and Aaron all served in World War I from Nebraska.

After his stint in Nebraska, Sam spent some time in Oklahoma. Oil had been discovered there, and Sam looked to invest. When his parents died in 1903 and 1907, he did not want the Illinois farm and inherited money instead. Mort’s children remembered that despite Sam’s high hopes, the oil play did not go well. Complicating the situation, Sam had become involved with a woman and then suspected her of wanting only his land and money. It is unclear whether or not he had married her. Mort finally travelled to Oklahoma to help resolve matters for his father. After this incident, Sam’s whereabouts are unknown, and he has not been positively identified on the 1920 U.S. census.

Later, after living in the western states for nearly 40 years, Sam returned to his home town when he was in his mid-seventies. In 1922 he began living with his eldest daughter Anna McDavitt and her family about 2 miles east of Ashmore, Illinois. Sometimes he experienced anxiety attacks and the urge to “go somewhere”. Other than that, he was in generally fair health although he had circulation problems and an enlarged prostate.

By 1927 he displayed more symptoms of age-related mental decline. He became increasingly wild and destructive around the house and did not keep himself clean. He suffered from hallucinations and chattered nervously about imaginary events. After an especially severe attack that required sedation, Anna realized she could no longer keep him at home. She had him declared incompetent, and committed him to the Jacksonville State Hospital for the Insane. There he died in his sleep a month later on October 2, 1928 at the age of eighty-three.

His body was returned to Ashmore for burial. His grandson Joseph VanMeter McDavitt (“Van”) earned $5 for cleaning up and readying the burial plot. After a funeral at the Baptist church with a Presbyterian minister officiating, Samuel was laid to rest in the Enon Cemetery next to his first wife Nancy and their daughters Amy and Mary Jane.

Sam’s estate consisted only of some money in the Ashmore bank. He had not led an industrious life, and most of his inheritance had been lost in poor land deals. After payment of his final expenses, $549.81 remained. Distribution to his nine surviving children amounted to $61.09 each, but Viola and Mort refused to accept their shares. They directed that their inheritance should go to Anna to compensate her for caring for their father.

Although Samuel did not leave large sums to his children, he did give them some valuable advice. They all remembered that he often said, “You inherited a good name, now keep it that way.” He may have wandered about and squandered his money, but he always kept what he valued most, his good name.

Thanks Teri, what a wonderful story.